Introduction: The Universal Challenge of Aging

Aging is the one biological certainty that unites all multicellular life, a universal, inevitable process characterized by the progressive decline in physiological function and increased vulnerability to disease. For centuries, the nature of aging was viewed through a macroscopic lens—the gradual failing of organs, the weakening of muscles, and the slowing of cognitive processes. However, in the 20th century, scientists began to realize that the secrets to aging and, potentially, its reversal were not found in the large, visible organs but in the microscopic, invisible mechanisms governing the life and death of individual cells. This exploration led to the discovery of cellular senescence, the point at which a cell permanently stops dividing, and the subsequent identification of the crucial biological markers that act as the cell’s own internal clock.

At the heart of this cellular timekeeping mechanism lies a remarkable structure known as the telomere. Telomeres are protective caps found at the ends of every chromosome, acting much like the plastic tips on shoelaces. Their primary job is to safeguard the precious genetic information during cell division. Yet, with every division, these protective caps inevitably shorten, acting as a countdown timer for the cell. Once the telomeres become critically short, the cell is forced into senescence or programmed death (apoptosis), preventing damaged DNA from being copied.

The revolutionary understanding that telomere length is a direct correlate of cellular age and disease risk has transformed gerontology and genetics. It has opened exciting avenues for intervention, particularly through the study of the enzyme telomerase, which can restore telomere length and potentially grant cells a form of immortality. While the science of radical life extension is still in its nascent stages, mastering the mechanics of telomere maintenance is central to understanding and eventually manipulating the core process of biological aging. This comprehensive guide will dissect the structure and function of telomeres, explore their direct link to chronic disease, and examine the groundbreaking research aimed at controlling this fundamental biological timer.

Section 1: The Molecular Structure and Function of Telomeres

Telomeres are non-coding, repetitive DNA sequences that play an essential protective role, yet their very mechanism of protection leads to their gradual demise.

A. Telomeres as Protective Caps

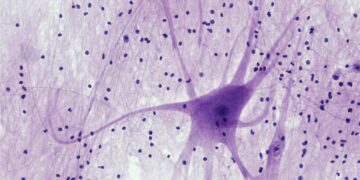

Telomeres are highly specialized DNA sequences located at the terminal ends of linear chromosomes in eukaryotic cells.

A. Repetitive Sequence: In humans, the telomere sequence is a simple, six-nucleotide repeat of TTAGGG that is repeated thousands of times, forming a long, redundant stretch of DNA.

B. Protecting the Code: Their primary function is to prevent the chromosome ends from being mistakenly recognized by the cell’s repair machinery as broken DNA. Without telomeres, the cell would attempt to “repair” the ends by fusing chromosomes together, leading to catastrophic genetic instability.

C. The T-Loop Structure: To enhance stability, the single-stranded overhang at the very end of the telomere often tucks back into the double-stranded region, forming a protective structure called the T-loop (Telomeric-loop), which is further stabilized by a protein complex known as Shelterin.

B. The End-Replication Problem

The structure of the telomere directly addresses a fundamental challenge inherent in DNA replication, known as the End-Replication Problem.

A. DNA Polymerase Limitation: The enzyme responsible for copying DNA, DNA Polymerase, can only synthesize a new DNA strand in one direction, and crucially, it requires a short RNA primer to start the process.

B. The Uncopied Gap: On the lagging strand during DNA replication, the primer at the very end of the chromosome cannot be replaced with DNA and leaves a small, uncopied gap.

C. The Shortening Cycle: Because of this limitation, a small portion of the telomere is lost with every cell division. The telomeres, therefore, act as a buffer zone to protect the actual coding genes from this inevitable loss.

D. The Hayflick Limit: Once the telomeres shorten to a critical length, the cell reaches the Hayflick Limit (named after Leonard Hayflick). The cell stops dividing, enters senescence, and signals its aged state to the body.

Section 2: Telomerase: The Enzyme of Immortality

While most cells experience inevitable telomere shortening, certain specialized cells possess the capacity to maintain or even restore their telomere length through the activity of a remarkable enzyme.

A. The Mechanism of Telomerase

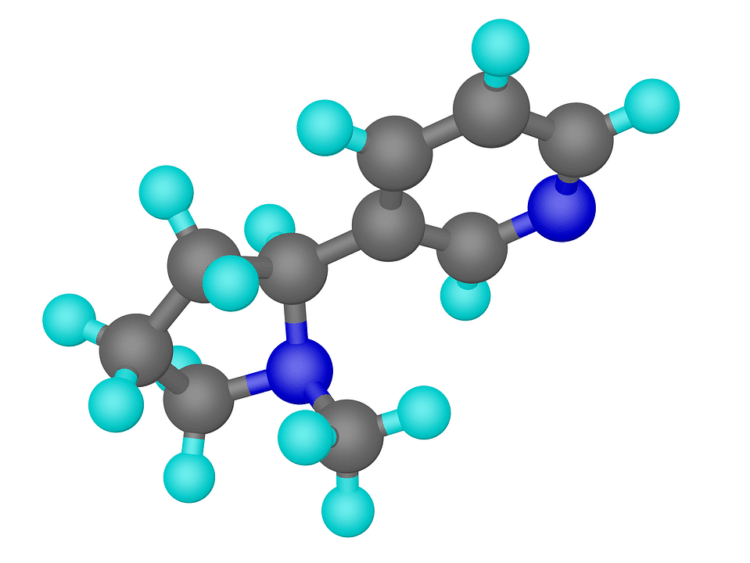

Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein enzyme that acts as a reverse transcriptase, capable of adding new repetitive sequences to the telomeres.

A. Ribonucleoprotein Structure: Telomerase is unique because it carries its own internal RNA template (TERC). This RNA template dictates the sequence (TTAGGG) that telomerase adds to the end of the chromosome.

B. Reverse Transcription: The enzyme uses its RNA template to synthesize a new DNA sequence, effectively extending the telomere, a process known as reverse transcription.

C. The Restoration: This action bypasses the end-replication problem, allowing the cell to maintain telomere length despite repeated divisions, effectively restarting the cellular clock.

B. Differential Expression in Cells

The key to aging lies in which cells express the telomerase enzyme and which do not.

A. Immortal Cells: Telomerase is highly active in germline cells (sperm and egg), ensuring that the genetic material passed to the next generation is fully intact with long telomeres. It is also highly active in stem cells, allowing them to divide indefinitely to replenish tissues.

B. Somatic Cells: In the vast majority of somatic cells (body cells), the telomerase gene is largely switched off or expressed at very low levels. This enforced repression is a crucial mechanism for limiting cell lifespan.

C. The Cancer Connection: Cancer cells represent a major exception. To achieve their uncontrolled, immortal growth, over of human cancers reactivate the telomerase enzyme. This discovery made telomerase a prime target for anti-cancer drug development.

D. Induced Expression: Scientists have demonstrated that activating telomerase in normal human somatic cells in vitrocan successfully extend their proliferative capacity, demonstrating the enzyme’s power to essentially immortalize the cells in a laboratory setting.

Section 3: Telomeres and the Burden of Disease

![]()

Telomere length is not just a marker of cellular age; it is increasingly recognized as a potent biomarker for the body’s overall biological age and a predictor of susceptibility to chronic disease.

A. Short Telomeres and Degenerative Disease

Critically short telomeres are associated with the failure of highly regenerative tissues and an increase in inflammation.

A. Cardiovascular Risk: Individuals with shorter-than-average telomeres for their chronological age have a statistically higher risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis, hypertension, and myocardial infarction (heart attack).

B. Neurodegenerative Conditions: Telomere shortening has been implicated in conditions related to aging brains, such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, particularly affecting neurons and glial cells.

C. Immunosenescence: Shortening telomeres in immune cells (lymphocytes) leads to immunosenescence, the gradual decline in immune system function, making the body less effective at fighting off new infections and monitoring for cancer cells.

D. Accelerated Aging Syndromes: Rare genetic disorders, known as telomeropathies (e.g., Dyskeratosis Congenita), involve defects in the telomerase enzyme or the Shelterin complex, leading to massively accelerated telomere shortening and premature aging in the affected individuals.

B. Environmental and Lifestyle Factors

Telomere length is not solely determined by genetics; it is highly susceptible to external and behavioral influences that affect the rate of attrition.

A. Oxidative Stress: Oxidative stress, caused by reactive oxygen species (free radicals), is a major accelerator of telomere shortening because it damages the DNA structure. Sources include pollution, smoking, and chronic inflammation.

B. Chronic Stress: Prolonged psychological stress has been shown in human studies to correlate with shorter telomere lengths, suggesting that stress hormones (like cortisol) negatively impact the cell’s ability to maintain its telomeres.

C. Diet and Nutrition: Diets rich in antioxidants and omega-3 fatty acids, often found in the Mediterranean diet, are associated with better telomere maintenance, supporting the idea that proper nutrition can slow cellular aging.

D. Physical Activity: Regular, moderate physical exercise is consistently linked to longer telomere lengths, likely by reducing oxidative stress and improving immune function.

Section 4: Therapeutic Strategies and Interventions

The recognition of telomeres as the central cellular clock has spurred intense research into strategies to therapeutically slow or reverse their shortening.

A. Telomerase Activation

The most direct approach to counter cellular aging is to temporarily and safely reactivate telomerase in somatic cells.

A. Gene Therapy Delivery: Researchers are exploring using gene therapy (often via viral vectors) to deliver the gene for the active telomerase subunit into specific tissues to lengthen telomeres.

B. RNA Modification: Another method involves introducing modified RNA templates directly into cells, temporarily boosting telomerase activity without permanently altering the cell’s genome, which may be safer than permanent gene insertion.

C. Small Molecule Activators: The holy grail is the discovery of small-molecule drugs that can safely and transiently increase the activity of the cell’s endogenous telomerase enzyme, without the risk of promoting cancer.

D. The Cancer Paradox: Any intervention that safely lengthens telomeres must be meticulously designed to avoid the critical risk of unintentionally immortalizing pre-cancerous cells. This paradox remains the largest hurdle to widespread human application.

B. Targeting Oxidative Stress and Inflammation

Since lifestyle factors influence telomere length through stress and inflammation, interventions focusing on these areas are essential complementary therapies.

A. Antioxidant Supplementation: While general antioxidant supplements have shown mixed results, targeted interventions aimed at specific cellular pathways involved in managing oxidative stress might prove more effective in protecting telomere DNA.

B. Inflammation Control: Chronic, low-grade inflammation is a hallmark of aging (inflammaging) and a key driver of telomere attrition. Strategies to reduce systemic inflammation (through diet or drug therapy) are vital anti-aging approaches.

C. Mitochondrial Health: The mitochondria are the cell’s energy powerhouses and the primary source of reactive oxygen species. Improving mitochondrial efficiency and reducing their stress output can indirectly protect telomere integrity.

Section 5: Ethical and Societal Implications of Life Extension

The mastery of telomere biology and the prospect of extending human lifespan significantly raise profound ethical and societal questions far beyond the laboratory.

A. The Challenge of Social Equity

Achieving radical life extension through telomere manipulation would likely be a resource-intensive technology, creating a major ethical challenge regarding access.

A. Elitism Risk: If life-extending therapies are prohibitively expensive, they would initially be available only to the wealthy elite, potentially leading to a sharp division between “mortals” and genetically enhanced, long-lived “immortals.”

B. Exacerbated Inequality: This would drastically exacerbate existing social and economic inequalities, granting a small percentage of the population an unprecedented biological advantage and creating new forms of discrimination.

C. Healthcare Mandate: Governments and international bodies would face immense pressure to ensure that foundational anti-aging therapies are treated as a public health mandate, not a luxury commodity.

B. Population and Resource Concerns

A dramatic increase in average human lifespan would instantly strain global resources and existing social systems.

A. Resource Scarcity: A significant extension of lifespan would increase global population density and consumption, putting unprecedented pressure on food supplies, water resources, and energy production.

B. Economic Instability: The entire economic structure is built on assumptions of retirement age, workforce turnover, and life expectancy. Extending the maximum lifespan would require a complete overhaul of pension systems, healthcare funding, and the job market.

C. Intergenerational Conflict: Longer lifespans could lead to increased tension and competition between generations, with older, experienced workers potentially blocking younger generations from career advancement and leadership roles.

C. Defining “Healthy Lifespan”

The scientific goal is not just to extend life, but to extend healthspan—the period of life spent in good health, free from chronic disease.

A. Avoiding Frailty: Simply extending the years of sickness and frailty would be a Pyrrhic victory. The focus must be on maintaining cellular function and vitality throughout the extended lifespan.

B. Quality of Life: Therapies must ensure the biological processes of the brain remain healthy, addressing the risk of neurodegenerative decline alongside cellular vitality in other tissues.

C. Evolutionary Impact: The long-term evolutionary consequences of eliminating or minimizing the natural aging process are entirely unknown, adding an element of profound uncertainty to the application of these powerful technologies.

Conclusion: The Horizon of Biological Control

![]()

Telomeres serve as the most visible, quantifiable expression of our cellular aging process, representing a key control point in the delicate balance between cell division and senescence. Scientific mastery of this system promises to rewrite the fundamental rules of biological decline.

Telomeres are the protective, repetitive DNA caps on chromosomes that shorten with every cell division, defining the cell’s lifespan.

The inevitable shortening is a direct consequence of the End-Replication Problem, where DNA polymerase cannot fully copy the very end of the lagging strand.

The enzyme Telomerase acts as the crucial restorative mechanism, adding new DNA repeats to the telomeres to maintain their length in immortal cells like germline and stem cells.

The repression of Telomerase in somatic cells is a fundamental protective mechanism against cancer, but its absence leads directly to cellular aging and immunosenescence.

Short telomeres are a powerful biomarker linked to increased risk for a host of age-related diseases, including cardiovascular failure and neurodegenerative conditions.

Lifestyle factors such as chronic stress and oxidative damage are known to accelerate the rate of telomere shortening, linking behavior directly to biological age.

Future therapeutic strategies aim to safely and transiently reactivate telomerase or mitigate chronic inflammation, but must carefully navigate the paradox of cancer risk.