Introduction: The Next Industrial Revolution

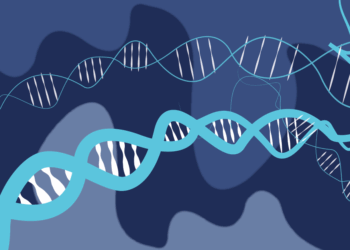

For millennia, human innovation has largely focused on manipulating the physical world—bending metal, harnessing fire, and generating electricity. However, the 21st century has ushered in a radical paradigm shift: the ability to design and construct biological components and systems that do not exist in nature, a discipline known as Synthetic Biology. Moving far beyond traditional genetic engineering, which merely transfers genes between existing organisms, synthetic biology treats DNA and cellular machinery as programmable parts, much like engineers use circuits and code. This approach applies the rigorous principles of engineering—standardization, abstraction, and modularity—to the messy world of living systems, aiming to create entirely new biological functions and organisms.

This foundational science promises to revolutionize nearly every sector of human activity, offering bespoke solutions that are inherently more sustainable, efficient, and clean than current chemical or industrial processes. Instead of relying on fossil fuels to synthesize complex chemicals or materials, synthetic biologists are programming microbes to act as tiny, self-replicating, sustainable factories. This has enormous implications for addressing some of the world’s most pressing challenges, from climate change and pollution to chronic disease and food security.

The ultimate goal of this field is the creation of a “synthetic chassis,” a minimal organism designed from the ground up that can be easily programmed to perform any desired task. This transition from reading life’s code to actively writing and editing it represents a new frontier, granting humanity unprecedented control over the fundamental processes of biology. This detailed exploration will unpack the core principles that guide synthetic biology, survey its groundbreaking applications in medicine, manufacturing, and environmental cleanup, and address the critical ethical and safety frameworks required to manage this immensely powerful technology responsibly.

Section 1: The Core Principles of Synthetic Biology

Synthetic biology relies on treating living cells not as mysterious black boxes but as complex, programmable systems, employing concepts borrowed directly from electrical engineering.

A. Standardization and Abstraction

To build reliable biological systems, components must be predictable, interchangeable, and follow standardized specifications.

A. BioBricks: Researchers established the concept of BioBricks, standardized DNA sequences (genetic parts) with defined functions and common assembly standards. These parts act like molecular LEGO blocks.

B. Modular Design: This allows synthetic biologists to create complex genetic circuits by snapping together multiple BioBricks, such as promoters, ribosome binding sites, and coding sequences, with the assurance that they will function predictably together.

C. Abstraction Hierarchy: The field uses an abstraction hierarchy, meaning researchers can focus on designing a high-level function (e.g., “produce insulin”) without needing to worry about the specific nucleotide sequence details, simplifying the process.

D. The Registry of Standard Biological Parts: International efforts maintain registries of these parts, fostering collaboration and accelerating the design phase of new biological systems.

B. The Design-Build-Test-Learn Cycle (DBTL)

The engineering approach requires a cyclical, iterative process to optimize the design and function of new biological circuits.

A. Design: Computational tools and sophisticated software are used to predict the optimal DNA sequence and circuit architecture required to achieve the desired function (e.g., producing a specific biofuel).

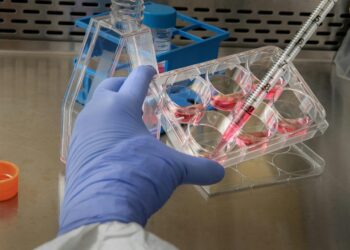

B. Build (Synthesis): The designed DNA sequence is chemically synthesized in a lab (often without needing a natural template) and then inserted into a host organism, typically a fast-growing bacterium like E. coli or yeast.

C. Test: The engineered organism is grown under controlled conditions, and its function is rigorously tested and measured. Does it produce the compound efficiently? Does the circuit switch on and off reliably?

D. Learn: The results from the testing phase are analyzed to understand why the circuit failed or succeeded. This knowledge is then fed back into the Design phase for iteration, ensuring continuous improvement and refinement.

C. Synthetic Genomes and Minimal Organisms

The pinnacle of synthetic biology involves the complete reconstruction or redesign of an entire living organism’s genetic code.

A. Total Genome Synthesis: Scientists have successfully synthesized the entire genome of a bacterium from scratch in a laboratory setting, effectively creating the first organism controlled by a totally synthetic genome.

B. Minimal Cell Concept: Research aims to determine the minimal genome—the smallest set of genes required for life under optimal laboratory conditions. This minimal organism serves as the ultimate “synthetic chassis,” free of unnecessary natural genes.

C. Optimized Host: A minimal cell is easier to understand, control, and program, reducing the unwanted interactions that often plague genetic engineering in natural, complex organisms.

Section 2: Healthcare and Therapeutic Applications

Synthetic biology is pioneering revolutionary methods for drug development, diagnosis, and the creation of intelligent, targeted cellular therapies.

A. Engineered Therapeutics

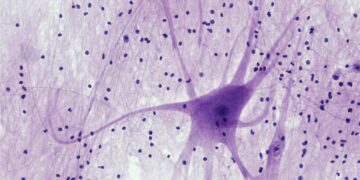

Microbes and mammalian cells can be programmed to act as living pharmacies or tiny diagnostic tools inside the body.

A. Living Diagnostics: Cells can be engineered with genetic circuits that act as sensors. For instance, a bacterium could be programmed to detect specific biomarkers (like low oxygen or high glucose) in the gut and then report the condition by changing color or producing a detectable signal.

B. Targeted Drug Delivery: Probiotic bacteria can be modified to reside in the digestive tract and produce therapeutic compounds (e.g., anti-inflammatory molecules) only when they detect a sign of disease, like a tumor or inflamed tissue.

C. Oncolytic Virotherapy: Viruses, which naturally target and replicate in cells, are being synthetically re-engineered to specifically infect and destroy cancer cells while leaving healthy cells untouched.

B. Vaccine and Drug Production

Synthetic biological techniques offer faster, cleaner, and more scalable ways to produce critical medical compounds.

A. Recombinant Drugs: Complex biological drugs, such as insulin and human growth hormone, are produced cheaply and in large quantities by engineering bacteria or yeast to express the human gene for that protein.

B. Rapid Vaccine Design: The principles of synthetic biology allow for the rapid design and synthesis of mRNA vaccines and other advanced vaccine platforms in response to emerging pandemic threats, accelerating the public health response time.

C. Complex Molecule Synthesis: Microorganisms are being engineered to produce rare, complex, high-value molecules that are difficult and expensive to synthesize chemically, such as the anti-malarial drug Artemisinin.

Section 3: Industrial and Sustainable Manufacturing

The greatest promise of synthetic biology lies in its potential to replace unsustainable fossil fuel-based manufacturing with clean, circular, and renewable bio-manufacturing.

A. Biofuels and Bioenergy

Programming microbes to efficiently convert common feedstock (like sugars or waste biomass) into high-energy fuels offers a sustainable alternative to petroleum.

A. Advanced Biofuels: Scientists are engineering yeast and bacteria to produce advanced liquid transportation fuels that are chemically identical to gasoline, diesel, or jet fuel, but derived entirely from renewable biomass.

B. Increased Yield: Genetic circuits are designed to redirect the host cell’s metabolic pathways away from producing natural byproducts and toward maximizing the yield of the desired fuel molecule.

C. Carbon Capture and Utilization (CCU): Some organisms are being engineered to metabolize directly from the atmosphere or industrial emissions, transforming this greenhouse gas into usable plastics or fuels.

B. Bio-Materials and Specialty Chemicals

Microbes are becoming the new standard for manufacturing everything from sustainable plastics to high-performance textiles.

A. Sustainable Polymers: Engineered microbes can produce high-quality, biodegradable polymers and plastics, reducing the reliance on petrochemicals and addressing the global plastic waste crisis.

B. Protein-Based Materials: Scientists have developed engineered yeast that produces the key protein found in spider silk, creating a scalable and sustainable source for this material, which is five times stronger than steel by weight.

C. Flavor and Fragrance: Microbes are programmed to produce complex flavor and fragrance molecules that were traditionally harvested from rare plants or synthesized using toxic chemical processes, resulting in cleaner, purer products.

Section 4: Environmental Remediation and Restoration

Synthetic organisms are being deployed as living environmental cleanup crews, addressing pollution and supporting ecosystem restoration.

A. Bioremediation of Pollutants

Microorganisms can be programmed to detect, degrade, and neutralize harmful pollutants in soil and water.

A. Plastic Degradation: Bacteria are being engineered with synthetic pathways that allow them to efficiently break down stubborn plastics, such as Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET), into harmless monomers that can be reused.

B. Oil Spill Cleanup: Organisms can be enhanced to rapidly metabolize hydrocarbons found in crude oil, greatly accelerating the natural recovery process following catastrophic oil spills.

C. Heavy Metal Sequestration: Synthetic circuits can be inserted into bacteria to sense toxic heavy metals (like mercury or arsenic) in groundwater and then bind them, effectively sequestering the pollutants for safe removal.

B. Biosensing and Monitoring

Engineered organisms are being used to provide real-time, high-sensitivity monitoring of environmental conditions.

A. Water Quality: Bacteria can be programmed to glow or change color when they detect pathogens or contaminants in drinking water, providing immediate, cost-effective alerts.

B. Soil Health: Synthetic microbes can monitor and report on nutrient levels, moisture, and the presence of agricultural pathogens in soil, allowing farmers to apply fertilizers and treatments only when and where they are needed.

C. Early Warning Systems: Entire microbial communities can be engineered to act as an environmental early warning system, detecting subtle shifts in temperature, acidity, or chemical concentration that signal ecological stress.

Section 5: Safety, Ethics, and Governance

The immense power to design life necessitates a robust framework of ethical consideration, safety protocols, and public dialogue to ensure responsible innovation.

A. Biosecurity and Dual-Use Risk

The ease of synthesizing and manipulating genetic material raises serious concerns about intentional misuse, known as biosecurity risks.

A. Ease of Access: As DNA synthesis becomes cheaper and easier, the technology becomes more accessible to individuals or groups who might misuse it to create harmful biological agents.

B. Dual-Use Dilemma: Many innovations have a dual-use potential; for example, engineering a microbe to be highly infectious for research purposes could be weaponized.

C. Screening and Regulation: Effective gene synthesis screening programs are crucial to monitor orders for specific, dangerous DNA sequences. International treaties and regulatory bodies must be established to track and control key synthetic biological components.

B. Containment and Horizontal Gene Transfer

Accidental release of a modified organism into the environment presents risks to existing ecosystems.

A. Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT): Engineered organisms could potentially transfer their synthetic genes to wild, natural bacteria through HGT, leading to unforeseen consequences in the ecosystem.

B. Genetic Firewalls: To prevent escape, synthetic biologists design genetic firewalls into their creations. For example, essential genes might be made dependent on a lab-supplied chemical, ensuring the organism dies if it escapes containment.

C. Biological Containment: Techniques like “kill switches”—genetic circuits that trigger cell suicide under specific environmental conditions (like high temperature or the absence of a signal)—are crucial for biological containment.

C. Ethical Acceptance and Public Engagement

The public acceptance of synthetically engineered life depends heavily on transparent communication and democratic governance.

A. Perceived Risk: The idea of “playing God” or “creating life” generates public apprehension. Scientists have a responsibility to clearly distinguish between creating completely new life forms and modifying existing ones.

B. Democratization: The development of DIY biology and community labs emphasizes the need for public education and the inclusion of diverse voices in determining the ethical boundaries of the research.

C. Patent and Intellectual Property: The debate over who owns the intellectual property rights to synthetically created life forms is complex and requires legal frameworks that balance innovation with public access and benefit sharing.

Conclusion: Engineering the Living World

Synthetic biology is driving a technological evolution that views biological systems as a revolutionary form of renewable, programmable technology. By applying engineering rigor to genetics, the field promises solutions that are cleaner, more efficient, and fundamentally more sustainable than chemical alternatives.

The core of synthetic biology involves designing and assembling standardized biological parts (BioBricks) using the rigorous Design-Build-Test-Learn cycle.

This approach allows researchers to create customized genetic circuits that impart entirely new, non-natural functions to living cells.

In medicine, engineered cells are being programmed to act as living diagnostics and to produce complex therapeutics, transforming drug delivery and disease detection.

The field offers a pathway to sustainable manufacturing by programming microbes to produce advanced biofuels and biodegradable polymers, moving away from fossil fuels.

Engineered microorganisms serve as powerful tools for bioremediation, capable of degrading tough pollutants like plastics and hydrocarbons in the environment.

Despite the promise, the technology carries inherent biosecurity risks and ethical concerns regarding the potential for misuse and unforeseen ecological impact.

Successful innovation relies on establishing robust genetic firewalls and strict containment protocols to ensure the safety of these powerful, self-replicating biological systems.