Introduction: Challenging the Fixed Brain Myth

For centuries, the prevailing belief in neuroscience was that the adult human brain was a largely fixed organ, fully formed and hardwired early in childhood. This perspective suggested that once past a certain critical age, the brain’s structure and functional capabilities were set in stone. The loss of neurons due to injury or disease was considered an irreversible catastrophe. This rigid view offered little hope for recovery after brain trauma or stroke, and it minimized the potential for lifelong learning and adaptation. This idea of the brain as an unchanging biological computer has been a major limiting factor in both therapeutic interventions and educational philosophy.

However, over the last few decades, a revolutionary concept has fundamentally dismantled this static model: Neuroplasticity, often referred to as brain plasticity. This term describes the remarkable, lifelong capacity of the brain to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections and strengthening existing ones. Neuroplasticity is the biological mechanism that allows the brain to heal, adapt to new environments, store new memories, and learn complex skills well into old age. It is the engine behind recovery from injury and the secret to cognitive resilience.

This realization has completely redefined our understanding of brain health and human potential, proving that the brain is not a static machine but a dynamic, constantly evolving landscape. Neuroplasticity is what allows professional musicians to allocate more brain area to their hands or helps a blind person use visual brain regions to process auditory or tactile information. Understanding this capacity is essential to developing new therapies for mental illness and maximizing our cognitive abilities throughout life. This comprehensive guide will explore the major types of neuroplasticity, detail the molecular and cellular mechanisms that drive these changes, and examine the powerful applications this knowledge holds for recovery, learning, and well-being.

Section 1: Decoding Neuroplasticity

Neuroplasticity is not a single process; it is an umbrella term encompassing several distinct ways the brain changes its physical structure and function in response to experience, learning, and injury. Understanding these forms is key to leveraging the brain’s full potential.

A. Types of Functional Plasticity

Functional plasticity refers to the brain’s ability to shift functions from a damaged area to an undamaged area. It also describes how the brain improves existing functions.

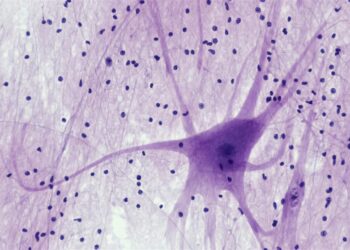

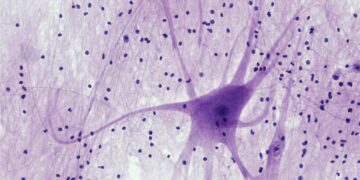

A. Synaptic Plasticity: This is the most fundamental and rapid type of plasticity. It involves changes in the strength of connections (synapses) between individual neurons. It is widely regarded as the cellular basis for learning and memory storage.

B. Functional Reorganization: If one part of the brain is damaged, neighboring or distant areas can gradually take over the lost function. For example, after a stroke damages the area controlling hand movement, other motor areas may compensate over time to restore partial function.

C. Cross-Modal Plasticity: This occurs when a brain region typically dedicated to one sensory modality (like sight) starts processing information from another modality (like touch or hearing). This phenomenon is commonly observed in individuals who are blind or deaf.

B. Types of Structural Plasticity

Structural plasticity involves physical, anatomical changes in the brain’s wiring, density, and overall architecture. These changes represent lasting physical transformation.

A. Neurogenesis: This is the rare but confirmed process of the brain producing new neurons. Although limited, it primarily occurs in the hippocampus, a region critical for forming new memories and learning.

B. Synaptogenesis and Pruning: Synaptogenesis is the formation of entirely new synapses or connections between neurons. Conversely, Synaptic Pruning is the removal of redundant or weak connections, a process crucial for optimizing neural networks and enhancing efficiency.

C. Angiogenesis: The brain can improve its physical structure by growing new blood vessels. This process, called angiogenesis, ensures that the newly active or forming neural networks receive adequate oxygen and nutrients to sustain their function.

D. Gliogenesis: The brain also changes the structure of its supporting cells, the glial cells (such as astrocytes and oligodendrocytes). These cells are essential for maintaining neural health and producing the myelin sheath that speeds up communication.

Section 2: The Molecular Engine of Change

The grand-scale changes observed in neuroplasticity are rooted in complex, minute processes occurring at the cellular and molecular levels. These molecular events translate experience into physical change.

A. Long-Term Potentiation (LTP)

The concept of Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) is the cellular mechanism widely accepted as the physical basis for learning and memory storage. It provides the biological explanation for how we remember things.

A. “Cells That Fire Together Wire Together”: This famous phrase summarizes the Hebbian principle proposed by Donald Hebb. When two connected neurons are repeatedly and simultaneously active, their synaptic connection is biologically strengthened.

B. Receptor Modulation: LTP involves increasing the number and sensitivity of receptors (specifically NMDA and AMPA receptors) on the receiving neuron (the postsynaptic cell). This makes the receiving cell much more responsive to future signals from the sending neuron.

C. Structural Change: Over the long term, LTP can cause the synapse to physically grow larger and more stable. The postsynaptic cell may develop new, mushroom-shaped extensions called dendritic spines to make the strong connection permanent.

D. Synaptic Strength: Essentially, LTP increases the efficiency of signal transmission across the synapse, transforming a quiet, unreliable connection into a strong, robust one.

B. Neurotrophic Factors

Specific proteins and growth factors in the brain act as molecular fertilizer. They promote the growth, differentiation, and long-term survival of neurons and their connections.

A. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF): This is one of the most critical molecules involved in plasticity. BDNF promotes the growth of new synapses, enhances the process of LTP, and stimulates neurogenesis in the hippocampus.

B. Activity Dependence: The production of BDNF is highly activity-dependent. Mentally stimulating activities and vigorous physical exercise both dramatically increase BDNF levels. This directly links our behavior to positive biological change in the brain.

C. Survival and Maintenance: Neurotrophic factors not only help build new connections but also ensure the long-term survival and healthy maintenance of existing neurons. They act as a crucial preventative shield against age-related degeneration.

D. Targeted Delivery: In therapeutic research, scientists are exploring ways to artificially increase BDNF in specific brain areas. This aims to maximize recovery following neurological events like stroke.

Section 3: Developmental and Critical Plasticity

Neuroplasticity is most profound during early life, but certain periods are especially marked by the brain’s ability to change dramatically. These windows of opportunity are critical for acquiring foundational skills.

A. The Plasticity of Childhood

The brain of an infant and child is vastly more plastic than that of an adult, a phase known as developmental plasticity. This allows for rapid learning.

A. Synaptic Overproduction: Early childhood is characterized by an explosion of synaptogenesis. The brain creates far more connections than it will ultimately need, maximizing its potential to adapt to any environment.

B. Experience-Dependent Pruning: As the child grows, the brain undergoes aggressive synaptic pruning. Connections that are frequently used become stronger and permanent, while those that are rarely used are eliminated. This sculpts a highly efficient, specialized adult brain.

C. Language Acquisition: This developmental phase explains why learning a new language or mastering a complex motor skill is significantly easier for young children. Their brains are fundamentally designed for rapid, large-scale reorganization.

D. Sensory Mapping: The detailed mapping of sensory areas, such as those for touch and hearing, occurs during this highly plastic period, fine-tuning the brain to its specific sensory input environment.

B. Critical Periods

Certain functions must be acquired during specific, limited time windows, or they become very difficult, if not impossible, to achieve later. These periods demonstrate the limits of adult plasticity.

A. Visual System Development: The development of the visual cortex has a strict critical period in early childhood. If a child’s vision is physically obstructed during this period, the visual cortex will fail to fully develop its necessary neural pathways. This leads to permanent visual impairment even after the physical obstruction is removed later in life.

B. Emotional Attachment: Early life experiences, particularly those related to secure emotional attachment and social bonding, profoundly influence the wiring of brain regions involved in emotional regulation. Disruption during this period can have long-lasting effects on mental health.

C. Window Closure: The molecular mechanisms that drive plasticity eventually slow down, causing the “window” of the critical period to close. Future research is intensely focused on the molecular brakes that close this window, aiming to safely and temporarily re-open these critical periods in adults to facilitate targeted therapeutic interventions.

Section 4: Plasticity in Repair and Rehabilitation

The most vital practical application of neuroplasticity is in facilitating recovery and adaptation following severe brain injury or sensory loss. It is the hope for millions of patients.

A. Stroke and Motor Recovery

Stroke causes rapid cell death due to lack of oxygen and nutrients, but the brain’s innate plasticity offers the main pathway for restoring lost motor function.

A. Peri-Lesional Compensation: After a stroke, the undamaged tissue immediately surrounding the lesion often reorganizes its function. It forms new connections and takes over some of the motor control functions previously managed by the damaged area.

B. Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT): This is a powerful, evidence-based therapy that exploits plasticity. It involves deliberately restraining the unaffected, healthy limb, compelling the brain to reorganize and strengthen the neural pathways associated with the weaker, stroke-affected limb.

C. Activity-Dependent Plasticity: Crucially, recovery is highly dependent on active, repetitive practice and training. The brain rewires itself only in response to specific, focused behavioral demand, emphasizing the patient’s role in their own healing.

D. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS): This non-invasive technique is sometimes used alongside physical therapy. It can selectively modulate the activity of cortical areas to prime the brain for more effective plastic change and functional recovery.

B. Sensory Substitution and Cross-Modal Plasticity

When one sense is lost, the brain often repurposes the vacant sensory processing real estate for enhanced use by the remaining senses. This shows remarkable resourcefulness.

A. Auditory Repurposing in Blindness: In individuals who are blind, parts of the occipital lobe normally dedicated to vision become active. This activation occurs when the person performs tasks requiring fine spatial or auditory processing, indicating the brain has successfully rerouted connections to the visual cortex.

B. Tactile Expansion in Deafness: Similarly, in deaf individuals, areas of the auditory cortex may be recruited to process tactile or visual input. This leads to enhanced skills, often improving lip-reading or sensitivity to vibrations.

C. Sensory Reorganization: This cross-modal plasticity highlights the brain’s resourcefulness and its primary biological priority. That priority is to use all available cortical tissue as efficiently as possible, regardless of its original genetic designation.

Section 5: Lifestyle, Cognition, and Neuroplasticity

Neuroplasticity is not just reserved for recovery from trauma; it is a mechanism we actively engage every day through our choices and mental habits. We are the architects of our own brains.

A. The Power of Learning

The acquisition of any new skill or piece of knowledge directly involves the physical rewiring of the brain. This is a fundamental law of learning.

A. Structural Growth: Learning a complex skill, such as juggling, playing a musical instrument, or navigating a large city, has been shown to result in measurable increases in gray matter density in the relevant cortical regions.

B. Skill Refinement: Expertise involves the brain becoming more efficient at processing the required information. Initial learning involves widespread, diffuse brain activity, but as the skill becomes automated, the activity becomes more focused and localized.

C. Maintaining Cognitive Reserve: Lifelong engagement in mentally challenging activities (e.g., puzzles, reading, learning a new language) builds a large cognitive reserve. This reserve provides alternative neural pathways that can buffer the effects of age-related brain deterioration or disease.

B. The Importance of Physical Exercise

Physical activity is one of the most potent, natural ways to stimulate neuroplasticity. The body and brain are deeply interconnected.

A. BDNF Release: Physical exercise, particularly aerobic exercise, leads to a significant and sustained increase in the expression of BDNF. This growth factor directly promotes both neurogenesis and synaptogenesis.

B. Improved Blood Flow: Exercise drastically improves cerebral blood flow. This ensures that active brain regions receive the increased oxygen and glucose they need to sustain high metabolic demand during learning and reorganization.

C. Stress Reduction: Exercise reduces chronic stress and inflammation, which are known to negatively impact neuroplasticity and neural health. By moderating stress hormones, exercise creates a healthier environment for neural growth.

D. Hippocampal Volume: Studies have shown that regular aerobic exercise can increase the physical volume of the hippocampus in older adults, a structural change directly related to improved memory function.

C. The Effects of Meditation and Mindfulness

Mental practices focused on attention and emotional regulation can induce measurable and lasting changes in brain structure and function. The mind can reshape the matter.

A. Cortical Thickening: Long-term meditators often show increased cortical thickness in areas associated with attention, introspection, and sensory processing. This suggests a physical thickening of the areas they intentionally exercise.

B. Amygdala Reduction: Consistent mindfulness practice is correlated with reduced gray matter density in the amygdala. This is the brain’s primary fear and stress center, leading to improved emotional regulation and a reduced stress response.

C. Functional Connectivity: Meditation alters the functional connectivity between the frontal executive centers and the emotional centers. This change enhances top-down cognitive control over emotional reactions, improving resilience.

Conclusion: Mastering the Flexible Mind

Neuroplasticity has demolished the outdated notion of a fixed adult brain, revealing our gray matter as an astonishingly dynamic organ capable of continuous adaptation. This ability to physically and functionally reorganize itself is the biological basis for human potential.

The foundation of this change is synaptic plasticity, primarily driven by mechanisms like Long-Term Potentiation (LTP), which strengthens neural connections through repeated use.

Structural changes involve neurogenesis (the growth of new neurons) and synaptogenesis (the formation of new connections), allowing the brain to physically rebuild.

The potent molecule BDNF acts as a molecular fertilizer, directly linking our behavior, such as physical exercise, to the promotion of neural growth and survival.

The brain exhibits its most dramatic changes during developmental critical periods, but this capacity persists into old age, fueled by lifelong learning.

Understanding plasticity is vital for recovery, enabling targeted therapies like Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) after a stroke.

The brain’s ability to repurpose tissue, known as cross-modal plasticity, allows remaining senses to compensate dramatically for a lost sense.