Introduction: The Architecture of Human Recall

Memory is not merely a passive storage vault for past events; it is a complex, dynamic, and fundamental cognitive function that defines our identity and enables us to navigate the world. Without the ability to form and retrieve memories, we would be trapped in a perpetual present, unable to learn from experience, recognize familiar faces, or plan for the future. For centuries, the nature of memory remained an elusive mystery, a kind of invisible psychological faculty divorced from physical biology. Yet, the devastating impact of amnesia, particularly the famous case of patient H.M., whose memory formation abilities were surgically destroyed, provided a critical, albeit tragic, clue.

The investigation into H.M.’s profound deficit, which left him unable to create new long-term memories but surprisingly intact in his ability to recall old ones, pointed directly to a specific, deep-seated brain structure. This structure, shaped like a seahorse and nestled deep within the medial temporal lobe of the brain, is the hippocampus. It became clear that the hippocampus acts as the crucial gateway through which raw sensory and emotional information must pass before it can be consolidated into stable, durable memories. Its role is not the final resting place of memories, but the temporary assembly site and conductor of the memory-making orchestra.

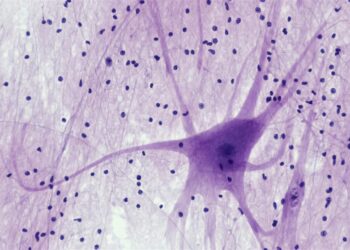

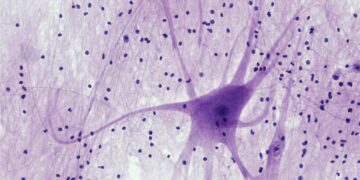

Understanding the hippocampus’s precise function—from receiving input from the sensory cortices to orchestrating the silent process of consolidation during sleep—is central to addressing memory disorders, cognitive decline, and developmental learning challenges. The delicate cellular mechanisms that occur within the hippocampus, specifically the strengthening of neural connections known as Long-Term Potentiation (LTP), reveal the physical, plastic nature of memory formation. This comprehensive exploration will dissect the anatomical structure of the hippocampus, detail its critical roles in memory processing and spatial navigation, and examine the profound implications of its health for learning and cognitive longevity.

Section 1: Anatomy and Location of the Hippocampus

The hippocampus is a small, evolutionarily ancient structure whose unique shape gives it its name, derived from the Greek words for “seahorse.”

A. Location within the Brain

The hippocampus is strategically positioned deep within the brain, placing it at the heart of many cognitive processes.

A. Medial Temporal Lobe: The structure is located in the medial aspect of the temporal lobe, tucked beneath the cerebral cortex. This location places it close to primary sensory and associative areas.

B. Paired Structures: Like most brain regions, the hippocampus is a paired structure, meaning there is one in the left hemisphere and one in the right hemisphere. Both sides typically work in coordination to process memories.

C. Input and Output Relay: Its location allows it to serve as a critical relay station. It receives extensive input from areas like the prefrontal cortex, the amygdala (emotion center), and the sensory association areas.

B. The Tri-Synaptic Circuit

The internal architecture of the hippocampus is defined by a specific, unidirectional flow of information known as the tri-synaptic loop. This loop is the functional engine of memory encoding.

A. Perforant Pathway to Dentate Gyrus: The flow begins with input from the entorhinal cortex, which enters the hippocampus through the perforant pathway and connects to the dentate gyrus. This is the first stop and is believed to be crucial for forming distinct new representations.

B. Mossy Fibers to CA3: The dentate gyrus neurons then project their signals (via mossy fibers) to the next subfield, known as CA3. The highly interconnected CA3 region is critical for pattern completion and recalling entire events from partial cues.

C. Schaffer Collaterals to CA1: Finally, the CA3 neurons project (via Schaffer collaterals) to the last subfield, CA1. CA1 acts as the critical output stage, transmitting processed information out to the rest of the cortex.

D. The Memory Loop: This highly organized, circular flow ensures that incoming information is processed sequentially, transforming transient sensory data into a coherent, nascent memory trace.

Section 2: The Critical Stages of Memory Formation

The hippocampus is primarily involved in the initial formation of new memories, a process that occurs in distinct stages following a learning event.

A. Encoding: The Initial Registration

Encoding is the initial process of converting external, sensory information into a mental construct that can be stored in the brain.

A. Attention Requirement: Effective encoding requires focused attention. If a person is distracted, the sensory information may reach the cortex but will fail to adequately activate the hippocampal loop.

B. Pattern Separation: The dentate gyrus is hypothesized to perform pattern separation. This is a critical function that ensures two highly similar events (e.g., parking your car in the same lot on two different days) are encoded as distinct, separate memories.

C. Association and Context: The hippocampus excels at binding together different features of an experience—the sight, the sound, the emotion, and the spatial context—into a single, unified episodic memory.

D. Rapid Learning: Encoding in the hippocampus is extremely rapid. A single, powerful event can be encoded almost instantly, unlike procedural skills which require many repetitions.

B. Consolidation: Stabilization and Storage

Once encoded, the memory trace is fragile and prone to disruption. Consolidation is the process by which this trace is stabilized and moved to long-term storage.

A. System Consolidation: This process involves a dialogue between the hippocampus and the neocortex. Over time, the hippocampus acts as the teacher, repeatedly reactivating the memory traces in the cortex until the cortex can recall the memory independently.

B. Role of Sleep: Consolidation is strongly associated with specific stages of sleep, particularly Slow-Wave Sleep (SWS). During SWS, the hippocampus replays the day’s events, transferring information efficiently to the cortical areas for permanent storage.

C. Temporal Gradient: The need for the hippocampus gradually diminishes over time. Newer memories are highly dependent on the hippocampus, while older, remote memories become independent, explaining why H.M. could recall childhood events but not recent ones.

D. Synaptic Consolidation: At the cellular level, this involves Long-Term Potentiation (LTP). The molecular changes at the synapse stabilize the connection, turning a temporary trace into a permanent physical change.

Section 3: Hippocampus and Different Memory Types

The hippocampus’s role is not universal; it is selectively involved in forming certain types of memory while leaving others untouched.

A. Explicit (Declarative) Memory

The hippocampus is the central hub for forming Explicit or Declarative memories—those memories that can be consciously recalled and verbalized.

A. Episodic Memory: This involves the recall of specific episodes or events from one’s life, complete with temporal and contextual details (e.g., what you ate for breakfast this morning or your last birthday party). The hippocampus is absolutely essential for forming these.

B. Semantic Memory: This involves the recall of facts, concepts, and general knowledge, independent of personal context (e.g., the capital of France or the function of a nucleus). While initially dependent on the hippocampus, semantic memories are ultimately stored primarily in the cortex.

C. Autobiographical Recall: The rich, complex memories of one’s own life heavily rely on the hippocampal binding of emotional and contextual information. Damage impairs the ability to construct a coherent life story.

B. Implicit (Non-Declarative) Memory

The hippocampus is largely uninvolved in the formation of Implicit or Non-Declarative memories, which are unconscious and expressed through performance.

A. Procedural Memory: This is the memory for skills and habits (e.g., riding a bike, typing, or playing the piano). These memories are primarily stored in the basal ganglia and cerebellum.

B. Priming: This involves unconscious exposure to one stimulus influencing a response to a subsequent stimulus. This relies on perceptual and cortical areas, not the hippocampus.

C. Classical Conditioning: Simple associative learning (e.g., Pavlov’s dogs) is mediated by pathways in the amygdala or cerebellum, demonstrating independence from the hippocampal system.

D. The H.M. Insight: Patient H.M. famously retained the ability to learn new motor skills and improve on certain tasks, despite his amnesia, solidifying the distinction between explicit and implicit memory systems.

Section 4: Hippocampus in Spatial Navigation

Beyond memory, the hippocampus plays a crucial and surprising role in spatial awareness and navigation, acting as the brain’s internal Global Positioning System (GPS).

A. The Cognitive Map Theory

Early research in rats established the hippocampus as the center for generating an internal, mental representation of the environment.

A. Place Cells: These are specific hippocampal neurons that fire vigorously only when an animal is in a precise, single location within a familiar environment. Together, these cells create a detailed cognitive map of the space.

B. Grid Cells (Entorhinal Cortex): Located in the adjacent entorhinal cortex, these cells fire when the animal is at multiple, regularly spaced locations, forming a triangular or hexagonal pattern. They provide the metric (distance and direction) for the cognitive map.

C. Boundary Cells: Found near the hippocampus, these cells fire when the animal is near a specific environmental boundary or wall, helping to anchor the internal map to the external world.

D. Virtual Navigation: Human studies using fMRI have confirmed that the hippocampus is highly active when people navigate complex, virtual environments, demonstrating that this function is conserved across species.

B. Implications for Human Navigation

The quality of an individual’s spatial memory and navigation skills is directly linked to the health and size of their hippocampus.

A. London Taxi Drivers: Studies of London taxi drivers, who must memorize the vast, complex street map of the city (“The Knowledge”), show they have significantly larger posterior hippocampi compared to control groups. This growth is directly proportional to the number of years spent driving the taxi.

B. Experience-Dependent Plasticity: This finding is a powerful demonstration of adult structural neuroplasticity. The constant demand of spatial navigation leads to the physical growth of the hippocampal region responsible for map storage.

C. Episodic and Spatial Link: It is hypothesized that episodic memory and spatial memory are deeply intertwined. Since every event occurs somewhere, the hippocampus evolved to encode where and when an event happened, binding context to episode.

Section 5: Clinical Significance and Hippocampal Health

The hippocampus is one of the most vulnerable brain regions, making its health a critical concern in major neurological and psychiatric disorders.

A. Hippocampal Vulnerability and Damage

Due to its high metabolic rate and critical placement, the hippocampus is susceptible to various forms of damage.

A. Alzheimer’s Disease: The hippocampus is one of the first brain regions to suffer significant damage from the toxic amyloid plaques and tau tangles characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. This explains why memory loss for recent events is the primary early symptom.

B. Chronic Stress and $\text{Cortisol}$: Prolonged exposure to high levels of the stress hormone cortisol can be neurotoxic to the hippocampus, leading to atrophy (shrinkage) and impaired neurogenesis. This link is prominent in conditions like Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and chronic depression.

C. Epilepsy: The hippocampus is a common focus for seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy. Repeated, uncontrolled seizure activity can cause structural damage (sclerosis) and lead to progressive memory impairment.

D. Anoxia/Hypoxia: Due to its high oxygen demands, the hippocampus is highly vulnerable to brain injury resulting from a temporary lack of oxygen (anoxia or hypoxia), such as from a near-drowning incident or severe cardiac arrest.

B. Promoting Hippocampal Resilience

Research has identified several lifestyle factors that can actively promote the health, size, and function of the hippocampus throughout life.

A. Physical Exercise: Aerobic exercise is one of the most effective non-pharmacological interventions. It significantly increases blood flow to the hippocampus and boosts the production of BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor), which supports neurogenesis.

B. Cognitive Reserve: Engaging in continuous intellectual stimulation (e.g., learning new languages, complex skills) builds a cognitive reserve. This helps the brain resist the functional effects of age-related hippocampal pathology.

C. Dietary Factors: Diets rich in antioxidants and Omega-3 fatty acids, such as the Mediterranean diet, are linked to larger hippocampal volumes and better cognitive function in old age.

D. Sleep Quality: Maintaining high-quality, sufficient sleep, particularly ensuring adequate Slow-Wave Sleep, is crucial for memory consolidation and for maintaining the integrity of hippocampal function.

Conclusion: The Seat of Self and Experience

The hippocampus stands as the ultimate convergence point for experience, emotion, and self-identity, serving as the essential, if temporary, seat of our episodic self. Without its diligent work, the continuous stream of conscious events would simply dissolve into the ether.

The hippocampus is a seahorse-shaped structure deep in the medial temporal lobe that acts as the brain’s essential memory formation center.

Its internal flow of information, the tri-synaptic loop, moves data from the entorhinal cortex through the dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1 subfields.

The structure is vital for encoding new memories and performing pattern separation to keep similar events distinct.

During sleep, the hippocampus orchestrates consolidation, transferring fragile new memories to the neocortex for long-term, permanent storage.

It is absolutely essential for the formation of explicit memories, specifically personal events (episodic) and factual knowledge (semantic).

The hippocampus is largely independent of implicit memories, such as procedural skills and simple habits, which are managed by other brain areas.

A critical, non-memory function is spatial navigation, achieved through specialized neurons known as place cells that create a mental map of the environment.

The hippocampus is the most vulnerable region to both Alzheimer’s disease and chronic stress, which leads to significant atrophy and memory loss.

Lifestyle factors such as aerobic exercise and cognitive engagement are crucial for boosting BDNF and maintaining the hippocampus’s volume and resilience throughout life.