Introduction: The Direct Link to Thought

For centuries, communication between the human mind and the external world has been mediated solely through the physical body—speech, gestures, and movement. This organic interface, however brilliant, presents severe limitations, especially when injury, disease, or extreme physical distance separates consciousness from the ability to act. The dream of bypassing the body entirely—of translating thought directly into action or data—was long relegated to the realm of science fiction and wild speculation. Today, that dream is rapidly becoming a reality through the groundbreaking field of Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs). BCIs, also known as Brain-Machine Interfaces (BMIs), represent a revolutionary technology that establishes a direct communication pathway between the brain’s electrical activity and an external device, such as a robotic arm, a computer cursor, or a speech synthesizer.

The fundamental principle is astonishingly simple yet technically complex: the BCI system must read the neural signalsgenerated by the brain, decode the user’s intent from those signals, and then translate that decoded intent into a command for the external technology. This process bypasses the spinal cord and peripheral nerves, offering an entirely new level of control for individuals who have lost motor function. The implications of this technology stretch far beyond therapeutic applications, promising to unlock new ways for all humans to interact with technology, potentially augmenting our cognitive and sensory capabilities.

From restoring the sense of touch to a paralyzed patient using a robotic hand to enabling rapid digital communication purely through mental command, BCIs stand at the very frontier of neurological science and engineering. This comprehensive exploration will detail the various methods BCIs use to capture neural activity, examine the critical challenges of decoding complex thoughts, survey the astonishing therapeutic breakthroughs already achieved, and discuss the profound ethical and societal questions that arise as we accelerate the integration of the human mind with machine intelligence.

Section 1: The Core Mechanisms of BCI Technology

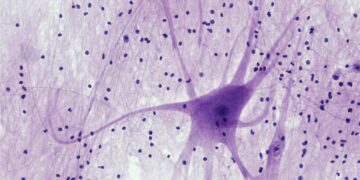

The foundational challenge of any BCI is obtaining clear, meaningful data from the brain. Different BCI types rely on varying degrees of invasiveness to achieve signal quality and fidelity.

A. Non-Invasive BCIs: External Reading

Non-invasive systems record brain activity from electrodes placed on the scalp, offering safety and ease of use, though signal clarity is reduced.

A. Electroencephalography (EEG): This is the most common and accessible non-invasive BCI method. EEG sensors placed on the scalp measure the summed electrical activity of millions of neurons, detecting large-scale brain waves associated with different mental states (e.g., attention, relaxation).

B. Signal Degradation: The major drawback of EEG is its low spatial resolution and its susceptibility to signal attenuation. The skull and intervening tissue dampen and scatter the electrical signals, making it difficult to pinpoint the activity of small, specific neural populations.

C. Event-Related Potentials (ERPs): Non-invasive BCIs often rely on specific, time-locked brain responses known as ERPs. A common example is the P300 speller, where the user focuses attention on a letter, causing a measurable P300 wave that the BCI uses to select the character.

D. Magnetoencephalography (MEG): MEG measures the magnetic fields generated by neural activity. While offering better spatial resolution than EEG, it requires massive, expensive equipment and a magnetically shielded room, limiting its practical use.

B. Invasive BCIs: Precision at the Source

Invasive systems require surgical implantation of electrodes directly into or onto the brain tissue, providing high-fidelity, high-resolution data.

A. ElectroCorticography (ECoG): ECoG electrodes are placed directly on the surface of the brain (the cortex), beneath the dura mater. This provides much clearer signals than EEG while still being less damaging than deep implants. It is often used in epilepsy patients.

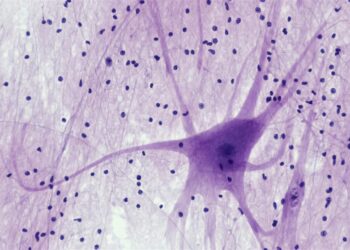

B. Microelectrode Arrays (MEAs): These are the most invasive and high-resolution systems. Arrays of tiny needles, such as the Utah Array or Neuropixels, are implanted directly into the gray matter, allowing the recording of activity from single or small groups of neurons with exquisite precision.

C. Neural Coding: MEAs are essential for understanding neural coding, as they can capture the specific firing patterns of individual motor neurons. This allows for fine-grained control of advanced prosthetics.

D. Risk vs. Reward: The clear advantage in signal quality comes with significant risks, including infection, immune response, and the potential for electrode drift or damage to brain tissue over time.

Section 2: The Decoding Challenge

Acquiring neural signals is only the first step; the true challenge lies in decoding the electrical noise into the user’s intended action or thought.

A. Decoding Motor Intent

The most successful BCI applications focus on decoding motor intentions from the motor and premotor cortices.

A. Population Vectors: The direction of an intended movement (e.g., reaching for a cup) is not encoded by a single neuron, but by the population vector—the combined, weighted activity of a large group of motor neurons, each tuned to a slightly different direction.

B. Calibration and Learning: The BCI must first be calibrated by having the user imagine a movement while the system learns the corresponding neural firing patterns. This process is highly personalized and requires machine learning algorithms.

C. Closed-Loop Feedback: For a BCI to be effective, it must operate in a closed-loop. The system receives a neural signal, translates it to a device action (e.g., the robotic arm moves), and the user receives visual and sensory feedback on the result, which in turn helps refine the neural signal.

D. Kinematic Decoding: Algorithms work to translate the raw neural activity into the kinematic parameters of movement, such as the velocity, trajectory, and endpoint of the intended action.

B. Decoding Cognitive States

Decoding non-motor, higher-order cognitive states, such as semantic concepts or emotional valence, remains a profound frontier.

A. Thought Translation: Researchers are beginning to decode the brain activity associated with specific silent speech or imagined words. This could allow paralyzed individuals to communicate at speeds far exceeding simple letter-by-letter spellers.

B. Memory Augmentation: BCIs could theoretically be used to reinforce the neural circuits involved in memory encoding (e.g., the hippocampus). This could potentially prevent the degradation of memory traces during consolidation, or even “write” new information into the brain.

C. Limitations of Localization: Unlike motor control, complex cognitive functions are highly distributed across the cortex. This makes it challenging to localize the signal source for specific thoughts or abstract concepts using current technology.

Section 3: Therapeutic Applications and Breakthroughs

BCIs have already transformed the lives of individuals with severe neurological impairments, offering unprecedented levels of independence and communication.

A. Restoring Motor Function

The most successful BCI applications focus on bypassing damaged sensory-motor pathways to restore control over physical devices.

A. Prosthetic Control: Paralyzed patients (e.g., those with $\text{ALS}$ or spinal cord injury) can use implanted microelectrodes to control advanced prosthetic limbs or functional electrical stimulation (FES) systems, allowing them to grasp objects and perform daily tasks.

B. Restoring Dexterity: Modern prosthetic control is moving beyond simple on/off commands. Sophisticated decoding allows for simultaneous control of multiple degrees of freedom, enabling movements approaching the dexterity of a human hand.

C. Wheelchair and Drone Control: Non-invasive EEG systems are increasingly being used to control wheelchairs and drones through specific cognitive tasks, such as imagining movements of the left or right hand.

D. Restoring Communication: BCI systems are allowing patients who are completely locked-in (fully aware but unable to move any muscles, including eyes) to communicate via typing or text-to-speech by decoding imagined handwriting or specific P300 signals.

B. Neuromodulation and Treatment

BCIs are also used not just to control external devices, but to directly modulate or regulate brain activity to treat neurological disorders.

A. Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS): While not strictly a BCI, modern DBS systems are becoming adaptive, recording brain activity and only delivering electrical stimulation (e.g., to treat Parkinson’s tremor or depression) when the pathological brain activity is detected.

B. Epilepsy Seizure Prediction: Advanced ECoG systems can monitor brain activity in real-time. Algorithms can learn to detect the early, subtle electrical signatures of an impending seizure, potentially delivering an immediate warning or preemptive therapeutic stimulus.

C. Pain Management: Research suggests BCIs could be used to train individuals to self-regulate the activity in brain regions associated with chronic pain perception, potentially offering non-addictive pain management strategies.

Section 4: The Push Towards Augmentation

Beyond therapeutic recovery, BCI technology is rapidly moving into the realm of augmentation—enhancing the cognitive and sensory capabilities of healthy individuals.

A. Enhancing Cognitive Abilities

Future BCIs aim to leverage the brain’s plasticity to make us smarter, faster, and more efficient thinkers.

A. Focused Attention: BCIs could be used in real-time to detect lapses in attention and deliver subtle, non-disruptive feedback (e.g., an auditory cue or mild vibration) to the user. This could help maintain focus during complex or monotonous tasks.

B. Accelerated Learning: If the neural correlates of successful memory encoding can be identified, a BCI could be used to stimulate the hippocampus with weak electrical currents during learning, thereby maximizing synaptic potentiationand accelerating memory formation.

C. Error Detection: Humans generate a characteristic signal called the Error-Related Negativity (ERN) when they recognize they have made a mistake. BCIs could track the ERN to provide immediate corrective feedback to a user, speeding up the trial-and-error learning process.

D. Direct Data Streaming: The ultimate augmentation goal is the ability to transfer large quantities of complex data directly from a computer to the cortex, effectively allowing us to download knowledge or skills, bypassing slow, traditional learning methods.

B. Augmented Sensory and Motor Control

BCIs promise new forms of interaction that expand our sensory and motor reach far beyond biological limits.

A. Third Arm Control: BCIs could allow a human to seamlessly control a third robotic arm in addition to their two biological arms. This would effectively multiply our physical capacity in manufacturing or hazardous environments.

B. Non-Biological Senses: The system could translate sensor data from infrared cameras or ultrasonic distance sensors into patterns of neural stimulation (e.g., tactile feedback or auditory cues). This would allow humans to perceive non-biological senses.

C. Shared Intelligence: Future BCIs could enable a form of shared consciousness or direct brain-to-brain communication, allowing two individuals to exchange thoughts, emotions, or complex mental models instantly and directly.

Section 5: Ethical, Safety, and Societal Frontiers

The power of BCIs is matched only by the complexity of the ethical and societal issues they raise, demanding careful and thoughtful regulation.

A. Safety and Biocompatibility

The long-term safety of implanted devices remains the most pressing technical challenge for invasive BCIs.

A. Immune Response: The brain views the implanted electrodes as foreign objects. Over time, the immune system walls off the electrodes with glial scar tissue, leading to signal degradation, a problem known as the biocompatibility challenge.

B. Long-Term Integrity: Electrodes must function flawlessly for decades. Failures, whether due to material degradation, power source exhaustion, or wire breakage, require complex and risky surgical replacement.

C. Data Security: The neural data recorded by BCIs is the most intimate and sensitive data imaginable. Protecting this information from hacking, misuse, or unwanted commercial exploitation is a severe biosecurity concern.

D. Invasive Necessity: The current trade-off between safety (non-invasive) and performance (invasive) means that high-fidelity systems are limited to severely disabled patients who accept the surgical risk.

B. Ethical and Rights Concerns

The ability to read and potentially modify thought raises fundamental questions about personal privacy and autonomy.

A. Cognitive Liberty: The concept of cognitive liberty asserts the right of individuals to control their own mental processes, consciousness, and neural data. BCIs challenge this liberty by making internal thoughts potentially readable.

B. Mental Manipulation: If BCIs can be used for deep brain stimulation, the potential for using them to non-consensually modify a person’s mood, behavior, or political beliefs raises the specter of mental manipulation and coercion.

C. The Digital Divide: As augmentation becomes commonplace, BCIs could create a dramatic new digital dividebetween those who can afford cognitive enhancement and those who cannot, potentially exacerbating social and economic inequalities.

D. Defining Personhood: If AI systems become integrated into the human brain, it complicates the legal and philosophical definition of personhood and autonomy. Where does the human stop and the machine begin?

Conclusion: Bridging the Human-Machine Gap

Brain-Computer Interfaces represent humanity’s boldest attempt to directly transcend our biological limits, ushering in an era of direct mental control over technology. This technology offers radical new hope for millions.

BCIs establish a direct communication pathway between the brain’s electrical signals and an external device, bypassing the physical body.

Non-invasive methods like EEG are safe but suffer from low signal resolution due to the filtering effect of the skull.

Invasive methods like Microelectrode Arrays (MEAs) provide high-fidelity, single-neuron data but require complex and risky surgery.

The central challenge is decoding motor intent from the complex population vector activity of thousands of motor neurons.

BCIs are already restoring independence, enabling paralyzed patients to control advanced prosthetic limbs and communicate via silent speech.

Therapeutic applications extend to neuromodulation, with adaptive DBS and seizure prediction systems offering precise treatment for neurological disorders.

The future goal is cognitive augmentation, aiming to accelerate learning, enhance attention, and potentially enable the direct transfer of data to the cortex.

Ethical frameworks must urgently address issues of cognitive liberty and the potential for a severe digital divide based on access to these powerful enhancements.

Ultimately, BCIs challenge us to redefine the boundaries of human identity and our relationship with the technology we create.