Introduction: Into the Abyssal Darkness

The human fascination with exploration has driven us to map continents, chart the skies, and even send probes to the furthest reaches of our solar system. Yet, ironically, the vast majority of our own planet remains fundamentally unknown, hidden beneath an immense curtain of water. More than 80% of the global ocean remains unmapped, unobserved, and unexplored, particularly the deep sea—the abyssal zone lying below 200 meters, where sunlight cannot penetrate. This immense volume of water, which constitutes the largest continuous ecosystem on Earth, is a realm of crushing pressure, perpetual darkness, and near-freezing temperatures. Despite these extreme conditions, the deep ocean harbors an astonishing diversity of life, defying our prior assumptions that life required warmth and light to flourish.

The challenges of exploring this realm are immense, requiring sophisticated and resilient technologies that can withstand pressures thousands of times greater than those at the surface. Every expedition into the deep sea is a complex logistical undertaking, a journey into a world governed by entirely different physical and biological rules. Our limited excursions have already revealed spectacular ecosystems, such as hydrothermal vents and cold seeps, where life is sustained by chemical energy rather than solar energy—a concept that has revolutionized our understanding of biology and the potential for life elsewhere in the universe.

The urgency to explore is heightened by global climate change and increasing demands for deep-sea resources. Understanding the baseline ecology of the deep ocean is crucial, as this zone plays a critical role in global biogeochemical cycles, including the regulation of carbon and heat. Without comprehensive mapping and biological surveys, we risk damaging delicate, slow-recovering ecosystems before we even know they exist. This extensive exploration will delve into the technological innovations that enable deep-sea access, detail the unique biological communities discovered, examine the critical role of the deep sea in planetary health, and discuss the frontier of deep-sea resource management and ethical exploration.

Section 1: The Harsh Realities of the Deep Ocean

The deep ocean is defined by three primary environmental extremes that shape the life forms and the technology required for exploration.

A. The Crushing Pressure Gradient

Pressure is the most significant physical barrier to both life and human exploration in the deep sea.

A. Atmospheres of Force: For every 10 meters of depth, the pressure increases by approximately one atmosphere (one bar). At the average abyssal depth of 4,000 meters, the pressure exceeds 400 atmospheres, equivalent to having the weight of an entire elephant resting on a postage stamp.

B. Technological Requirements: Submersible vehicles and instrumentation must be constructed with incredibly resilient materials, such as thick titanium or specialized ceramics. These materials are engineered to maintain structural integrity under this immense stress.

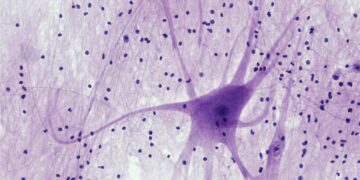

C. Biological Adaptations: Deep-sea organisms have evolved unique mechanisms to cope. They lack internal air spaces (like lungs) that would collapse, and their proteins and cell membranes are specially adapted to function stably under high pressure, preventing their molecular structures from deforming.

B. Perpetual Darkness and Cold

Below the photic zone (around 200 meters), the ocean plunges into eternal night and near-freezing temperatures.

A. The Photic Zone Limit: Sunlight is absorbed by the water column rapidly, meaning that photosynthesis, the basis of most surface life, is impossible below this depth. This creates a vast, energy-starved environment.

B. Temperature Stability: In the abyssal plains, the water temperature is typically cold and highly stable, hovering around $2^\circ \text{C}$ to $4^\circ \text{C}$. This stability leads to organisms with extremely slow metabolic rates and long lifespans.

C. Bioluminescence: Since external light is absent, many deep-sea creatures use bioluminescence—the production of light through chemical reaction—for communication, hunting (attracting prey), and defense (camouflaging or startling predators).

D. Sensory Evolution: Deep-sea fish often have massive eyes adapted to catch the tiniest flicker of bioluminescence. Other species forgo eyes entirely, relying instead on highly sensitive lateral lines and chemosensory organs to navigate and locate food.

Section 2: Technology Pushing the Limits of Access

Overcoming the physical barriers of the deep sea requires a diverse and specialized fleet of advanced robotic and submersible systems.

A. Manned and Unmanned Vehicles

Exploration relies on both highly specialized human-occupied vehicles and increasingly sophisticated robotic submersibles.

A. Human-Occupied Vehicles (HOVs): HOVs like the famous Alvin or the DSV Shinkai 6500 carry human observers to directly witness deep-sea phenomena. The experience gained by human intuition remains invaluable, though their time underwater is limited.

B. Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs): ROVs are tethered, unmanned robots controlled by operators on a surface ship. They offer longer mission durations and can carry heavy instrumentation, but their movement is constrained by the physical tether.

C. Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs): AUVs are pre-programmed, untethered robots. They offer the greatest spatial freedom, often used for long-distance bathymetric mapping and wide-area environmental sensing.

D. Hybrid Vehicles: Modern designs are moving towards hybrid systems that can operate in both tethered (ROV) and untethered (AUV) modes, maximizing both control and range during an expedition.

B. Mapping and Sensory Tools

To truly map the “uncharted territory,” exploration requires tools that can penetrate the darkness and chart the seafloor.

A. Multibeam Sonar: This technology uses acoustic pulses sent in a wide fan shape to measure the depth of the seafloor across a wide swath. Multibeam sonar is the fundamental tool for creating high-resolution bathymetric maps(underwater topography).

B. Synthetic Aperture Sonar (SAS): SAS provides high-resolution imagery of the seafloor, often used by AUVs to detect geological features or specific biological communities with centimeter-level precision.

C. Chemical and Geophysical Sensors: Modern deep-sea robots carry sensors to measure crucial environmental parameters in real-time. These include temperature, salinity, oxygen saturation, methane concentration, and $\text{pH}$levels.

D. Environmental DNA (eDNA): A revolutionary sampling method involves collecting water samples and analyzing the trace genetic material (DNA) left behind by organisms. This allows scientists to identify the diversity of life in an area without physically capturing the creatures themselves.

Section 3: Extraordinary Deep-Sea Ecosystems

The most scientifically significant discoveries in deep-sea exploration have centered on unique ecosystems that thrive independently of solar energy.

A. Chemosynthetic Communities

The discovery of hydrothermal vents in 1977 completely overturned biological dogma, proving that life could exist powered by Earth’s internal heat and chemistry.

A. Hydrothermal Vents: These are cracks in the seafloor, often found near tectonic plate boundaries, where superheated water (up to $400^\circ \text{C}$), rich in dissolved minerals (sulfides, iron), spews out from the crust.

B. Chemosynthesis: The primary producers here are not plants, but specialized chemosynthetic bacteria. These microbes use chemical energy (from oxidizing hydrogen sulfide, for example) instead of light energy to create organic matter.

C. Trophic Abundance: These bacteria form the base of a dense, thriving food web. This unique ecosystem supports spectacular species like giant tube worms, vent shrimp, and blind crabs, all adapted to the toxic, superheated environment.

D. Duration and Transience: Vent systems are geologically ephemeral, sometimes only active for a few years or decades. The speed with which specialized vent fauna colonize new vent sites remains a key area of study.

B. Cold Seep Ecosystems

Similar to vents, cold seeps host chemosynthetic life but are driven by different chemical sources and operate at lower temperatures.

A. Methane and Oil: Cold seeps occur where hydrocarbons (methane gas or crude oil) leak slowly from the seafloor. Chemosynthetic microbes use the energy in these reduced compounds.

B. Biological Mats and Clams: These seeps are characterized by thick mats of white or colorful chemosynthetic bacteria and unique communities of large, slow-growing clams and mussels that host symbiotic bacteria within their tissues.

C. Extremely Slow Growth: Due to the low temperatures and slower flux of chemical energy, organisms in cold seeps often have exceptionally long lifespans, sometimes living for hundreds of years.

D. Brine Pools: A unique type of seep is the brine pool, a dense, super-salty pocket of water settled in depressions. These areas often appear like surreal, alien lakes on the seafloor.

Section 4: The Deep Ocean’s Role in Planetary Health

The deep sea is not merely a collection of isolated ecosystems; it is a critical regulator of global climate and nutrient cycling.

A. The Global Carbon Sink

The deep ocean plays the dominant role in absorbing and sequestering carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

A. The Biological Pump: This process involves phytoplankton near the surface converting $\text{CO}_2$ into organic matter. When these organisms die, they sink as marine snow to the deep ocean, carrying carbon with them.

B. Long-Term Sequestration: The carbon that reaches the deep abyssal plains can be locked away in sediments for thousands of years. This long-term sequestration is vital for regulating atmospheric $\text{CO}_2$ levels.

C. Vulnerability: Disturbing the deep-sea floor, such as through deep-sea mining, could re-suspend this sequestered carbon and potentially interfere with the efficiency of the biological pump.

B. The Ocean Conveyor Belt

Deep ocean currents are essential components of the Thermohaline Circulation, which distributes heat and nutrients around the globe.

A. Deep Water Formation: Cold, dense, oxygen-rich water sinks in key areas (like the North Atlantic) and flows along the seafloor, slowly replenishing oxygen in the deep basins over millennia.

B. Nutrient Recycling: This circulation eventually brings nutrient-rich deep water back up to the surface (upwelling) in other regions, fertilizing surface waters and supporting major global fisheries.

C. Climate Link: Changes in surface temperature and salinity, such as those caused by melting ice sheets, can disrupt this deep circulation, impacting global climate patterns, as explored in the context of the AMOC (Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation).

Section 5: The Future of Deep-Sea Exploration and Stewardship

Increasing technological capability and resource scarcity are pushing humanity to consider the deep sea as a new economic and resource frontier, raising profound stewardship challenges.

A. Deep-Sea Mining: The New Gold Rush

Vast mineral deposits on the seafloor are attracting commercial interest, creating a new urgency for governance and scientific assessment.

A. Polymetallic Nodules: These potato-sized rocks, rich in manganese, iron, nickel, copper, and cobalt (essential for high-tech batteries), cover large areas of the abyssal plains.

B. Hydrothermal Sulfides: Deposits around inactive hydrothermal vents contain high concentrations of gold, silver, copper, and zinc.

C. Environmental Risk: Mining the seafloor involves scraping or vacuuming large swaths of the abyssal plain. This process creates vast sediment plumes that smother deep-sea organisms and their habitats, which are known to recover extremely slowly.

D. The Precautionary Principle: Environmental groups and some scientists advocate for a temporary moratorium on deep-sea mining, arguing that the Precautionary Principle must apply. We should not damage ecosystems before their biodiversity is fully mapped and understood.

B. International Governance and Marine Protected Areas

The high seas—waters beyond national jurisdiction—cover over $60\%$ of the planet, making their regulation a matter of international cooperation.

A. ISA (International Seabed Authority): The $\text{ISA}$ is the UN-mandated body responsible for regulating mineral-related activities in the international seabed area. Its dual mandate is to protect the marine environment while also regulating deep-sea mineral exploration.

B. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs): Scientists are urging the designation of extensive Deep-Sea Marine Protected Areas (D-MPAs) to safeguard vulnerable habitats like hydrothermal vents and unique seamounts from resource exploitation.

C. The BBNJ Treaty: The recent $\text{UN}$ High Seas Treaty (often called $\text{BBNJ}$, for Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction) aims to establish a legal framework for the conservation and sustainable use of marine life in areas outside national control.

D. Open-Source Data: Promoting global collaboration and open-source data sharing of bathymetric maps and biological surveys is crucial to accelerating the mapping of the remaining unknown ocean floor.

Conclusion: Stewardship of the Abyssal Realm

The deep ocean, Earth’s largest remaining frontier, is a cold, dark, and highly pressurized world that plays a disproportionately large role in planetary stability. It must be explored with both rigor and responsibility.

The deep sea, below 200 meters, remains over $80\%$ unexplored, defined by crushing pressure and perpetual darkness.

Exploration relies on advanced robotics, including tethered ROVs and untethered AUVs, built to withstand extreme environments.

Multibeam sonar is the essential technology used to create high-resolution maps of the hidden seafloor topography.

The discovery of hydrothermal vents proved that life can thrive through chemosynthesis, powered by chemical energy from the Earth’s interior.

These unique deep-sea ecosystems support strange life forms like giant tube worms and blind shrimp, adapted to toxic conditions.

The deep ocean acts as the Earth’s most important climate regulator, sequestering atmospheric carbon via the biological pump.

Deep-sea currents are vital, driving the thermohaline circulation that distributes heat and oxygen globally.

The emergence of deep-sea mining for polymetallic nodules presents a critical conflict between resource demand and environmental protection.

International bodies like the ISA and new treaties must establish governance to ensure that exploration precedes, and ethically informs, exploitation.

Ultimately, effective stewardship of the abyssal realm is key to maintaining global marine health and climate stability.