Introduction: The Disturbed Equilibrium of Life

The carbon cycle is one of Earth’s most fundamental biogeochemical processes, acting as the planet’s thermostat and the backbone of all known life. For billions of years, a delicate and dynamic equilibrium existed, wherein carbon flowed naturally between the atmosphere, oceans, terrestrial biosphere, and geological reservoirs. Trees and phytoplankton absorbed carbon dioxide ($\text{CO}_2$), animals released it through respiration, the oceans absorbed it, and geologic processes slowly locked it into rocks and sediments. This perfect balance maintained atmospheric $\text{CO}_2$concentrations within a stable range, creating the habitable climate that allowed human civilization to flourish over the last 10,000 years. However, in a startlingly short period—primarily since the Industrial Revolution—human activity has profoundly disrupted this ancient equilibrium, initiating a genuine planetary crisis.

By extracting and burning vast quantities of fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas) that were stored deep underground for millions of years, we are rapidly releasing colossal amounts of long-sequestered carbon back into the active cycle. This sudden, massive input of $\text{CO}_2$ has overwhelmed the natural capacity of the oceans and biosphere to absorb the excess gas. The result is the accelerated greenhouse effect, driving global warming, extreme weather events, and ocean acidification. Consequently, restoring the stability of the carbon cycle has become the defining scientific and political challenge of our era, demanding a radical two-pronged strategy: drastically reducing the emission of new carbon and aggressively sequestering (or removing) the legacy carbon already accumulated in the atmosphere.

This essential global effort encompasses technological innovation, from large-scale engineered carbon capture systems to nature-based solutions like reforestation and regenerative agriculture. Understanding the complex mechanisms by which we can stabilize the climate requires a deep dive into the various reservoirs where carbon resides and the pathways we must enhance or invent to move carbon back out of the atmosphere. This extensive exploration will detail the natural carbon cycle, pinpoint the human perturbations that caused the current crisis, examine the spectrum of available reduction and sequestration strategies, and discuss the profound policy and technological shifts required to secure a balanced climate future.

Section 1: The Natural Carbon Cycle Explained

The carbon cycle involves the continuous movement of carbon atoms among four major interconnected reservoirs, or spheres.

A. The Four Major Reservoirs (Spheres)

Carbon is stored in different forms and quantities across the Earth system.

A. Atmosphere: Carbon exists primarily as carbon dioxide ($\text{CO}_2$), a potent greenhouse gas. This reservoir is the smallest but is the fastest-growing due to human activity.

B. Hydrosphere (Oceans): The oceans hold the largest quantity of actively cycling carbon, primarily as dissolved inorganic carbon (bicarbonate and carbonate ions). The ocean absorbs about $30\%$ of the $\text{CO}_2$ emitted by humans.

C. Terrestrial Biosphere: This reservoir includes all living and dead organic matter on land, such as trees, plants, soil organic matter, and animals. Forests are immense carbon sinks.

D. Lithosphere (Geosphere): This is the largest reservoir, containing carbon locked up in sedimentary rocks (like limestone) and in fossil fuel deposits. Carbon enters this reservoir slowly through weathering and deep-sea burial.

B. Pathways of Natural Exchange

Carbon moves between these reservoirs through various biological, chemical, and geological processes.

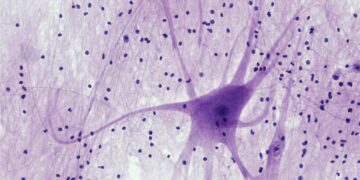

A. Photosynthesis: Plants and algae absorb $\text{CO}_2$ from the atmosphere or water to create carbohydrates. This moves carbon from the atmosphere into the biosphere, forming the fundamental biological link in the cycle.

B. Respiration and Decay: All living organisms, including plants, release $\text{CO}_2$ back to the atmosphere through respiration. Decomposition of dead organic matter by microbes also releases carbon back to the atmosphere and soil.

C. Ocean Exchange: $\text{CO}_2$ dissolves directly into the ocean surface and is released back out in a two-way gas exchange process. This process is driven by the difference in $\text{CO}_2$ concentration between the air and the water.

D. Weathering and Burial: Over vast timescales, atmospheric $\text{CO}_2$ combines with water to form a weak acid that slowly dissolves rocks. The resulting carbon ions are carried to the ocean and eventually deposited as carbonate sediments on the seafloor, locking carbon into the lithosphere.

Section 2: Human Perturbation: The Carbon Crisis

The stability of the natural cycle has been completely upended by the rapid human release of geologically stored carbon.

A. Fossil Fuel Combustion

The primary source of excess $\text{CO}_2$ is the burning of materials that represent ancient, sequestered carbon.

A. Ancient Carbon Release: Fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas) are the chemically altered remains of ancient plants and animals. Burning these fuels rapidly reverses the slow geological process, releasing millions of years of stored carbon in seconds.

B. Industrial Scale: Since the late $18^{\text{th}}$ century, the scale of industrial fossil fuel consumption has increased exponentially. This has resulted in the injection of billions of tons of $\text{CO}_2$ annually into the atmosphere.

C. Atmospheric Concentration Rise: This influx has pushed atmospheric $\text{CO}_2$ concentrations from the pre-industrial level of $280$ parts per million (ppm) to well over $420$ ppm today, fundamentally changing the radiative balance of the planet.

D. Greenhouse Effect Amplification: The increased $\text{CO}_2$ acts like a blanket, trapping heat in the lower atmosphere—the enhanced greenhouse effect—which is the direct cause of global warming.

B. Land Use Change

Human modification of the terrestrial biosphere has also shifted it from being a strong carbon sink to a carbon source.

A. Deforestation and Burning: Clearing forests, especially tropical rainforests, through logging and burning, immediately releases the large amount of carbon stored in the trees back into the atmosphere.

B. Soil Carbon Loss: Practices like intensive agriculture, deep plowing, and draining peatlands significantly accelerate the decomposition of organic matter in the soil, leading to the rapid loss of soil carbon to the atmosphere.

C. Loss of Natural Sinks: By destroying natural ecosystems, humans reduce the overall capacity of the terrestrial biosphere to absorb $\text{CO}_2$ through ongoing photosynthesis.

D. Cement Production: Another significant non-combustion source is cement production. Heating limestone ($\text{CaCO}_3$) to create clinker releases $\text{CO}_2$ as a chemical byproduct.

Section 3: Strategies for Carbon Reduction (Mitigation)

The first, most critical pillar of addressing the carbon crisis is rapidly eliminating the sources of new $\text{CO}_2$emissions.

A. Transition to Renewable Energy

Decarbonization of the energy sector is the single most important action to reduce emissions.

A. Renewable Deployment: This involves the massive, rapid global deployment of low-carbon energy sources, primarily solar photovoltaics and wind power, to replace coal and gas-fired power plants.

B. Grid Modernization: Modernizing the electrical grid to handle distributed and intermittent renewable energy requires significant investment in smart grid technologies, demand response, and high-capacity transmission lines.

C. Energy Storage: To ensure baseload reliability, the transition requires gigawatt-scale energy storage solutions, including utility-scale batteries (lithium-ion, flow batteries) and pumped hydro storage.

D. Nuclear Power: In many regions, nuclear power is considered a crucial low-carbon, baseload source to complement intermittent renewables, despite political and waste disposal concerns.

B. Decarbonizing Transportation and Industry

Reducing emissions from sectors difficult to electrify requires advanced technological solutions.

A. Electric Vehicles (EVs): The transition of passenger and commercial transport fleets to electric vehicles powered by clean electricity is essential to eliminate petroleum consumption in this sector.

B. Sustainable Fuels: For heavy-duty shipping, aviation, and long-haul trucking, which are challenging to electrify, the focus shifts to sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs), biofuels, and green hydrogen ($H_2$).

C. Green Hydrogen: Hydrogen produced via electrolysis powered by renewable energy (green hydrogen) can be used to decarbonize industrial processes like steel, ammonia, and cement production, which require very high heat.

D. Energy Efficiency: Implementing aggressive energy efficiency measures—such as building insulation, high-efficiency appliances, and industrial process optimization—reduces overall energy demand, thereby reducing the scale of the transition required.

Section 4: Nature-Based Carbon Sequestration

Nature itself provides the most immediate, scalable, and cost-effective pathways for removing $\text{CO}_2$ from the atmosphere.

A. Reforestation and Afforestation

Trees are the Earth’s natural carbon capture technology, pulling $\text{CO}_2$ from the air and storing it as biomass.

A. Reforestation: This involves planting trees on land that was previously forested but has been cleared. This restores the land’s natural carbon storage capacity.

B. Afforestation: This involves planting trees in areas that have not been historically forested, such as degraded land, to create new carbon sinks.

C. Forest Management: Improved forest management practices, including reducing illegal logging and actively suppressing devastating wildfires, help maintain the carbon stored in existing forests.

D. Blue Carbon: Protecting and restoring coastal ecosystems like mangrove forests, seagrass meadows, and tidal marshes—known as blue carbon ecosystems—is vital because these environments sequester carbon at rates even higher than terrestrial forests.

B. Agricultural and Soil Carbon Storage

The world’s agricultural soils have a massive, untapped potential for storing carbon.

A. Regenerative Agriculture: This umbrella term describes farming practices that focus on soil health. Techniques like no-till farming and reduced tillage disturb the soil less, retaining its carbon content.

B. Cover Cropping: Planting non-cash cover crops (e.g., clover, rye) after harvesting the primary crop keeps roots in the ground year-round. These roots continuously pump carbon into the soil.

C. Rotational Grazing: Implementing holistic rotational grazing systems for livestock, which mimic natural grazing patterns, can significantly enhance grass growth and root mass, thereby increasing soil carbon sequestration.

D. Biochar Application: Biochar is a stable, carbon-rich solid produced by heating biomass in the absence of oxygen (pyrolysis). Adding biochar to agricultural soils can lock carbon away for hundreds to thousands of years while improving soil fertility.

Section 5: Engineered Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR)

To achieve net-zero emissions, large-scale, engineered solutions are required to actively pull legacy $\text{CO}_2$ out of the atmosphere.

A. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS)

$\text{CCS}$ focuses on capturing emissions at large, stationary industrial sources before they ever reach the atmosphere.

A. Point-Source Capture: $\text{CCS}$ involves capturing $\text{CO}_2$ directly from the smokestacks of industrial facilities (like cement plants or power plants) using chemical solvents or membrane technologies.

B. Transportation and Injection: The captured, pressurized $\text{CO}_2$ is then transported, usually via pipelines, to suitable geological formations for permanent storage.

C. Geological Storage: The $\text{CO}_2$ is injected deep underground into porous rock layers, such as depleted oil and gas reservoirs, deep saline aquifers, or unmineable coal seams, where it is securely trapped.

D. Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR): In some cases, captured $\text{CO}_2$ is injected into existing oil fields to push remaining crude oil out. While generating revenue, this offsets the climate benefit unless the EOR process is managed strictly.

B. Direct Air Capture (DAC)

$\text{DAC}$ is a technological process designed to remove $\text{CO}_2$ directly from the ambient air, regardless of the source.

A. Chemical Absorption: $\text{DAC}$ plants use large fans to pull ambient air across specialized chemical filters or liquid solvents that selectively bind with the $\text{CO}_2$ molecules.

B. Regeneration and Release: The filter material is then heated (a high-energy step) or exposed to a vacuum to release the concentrated $\text{CO}_2$, which is then compressed and stored geologically.

C. Scaling Challenge: $\text{DAC}$ offers true carbon removal but is currently extremely expensive and energy-intensive because $\text{CO}_2$ is very dilute in the ambient air. Scaling this technology is a major global goal.

D. Carbon Mineralization: A permanent, albeit slow, form of geological storage is carbon mineralization, where captured $\text{CO}_2$ is injected into reactive rocks (like basalt or peridotite) and chemically reacts to form solid carbonate minerals.

Section 6: Policy, Economics, and Global Cooperation

Successfully implementing these reduction and removal strategies requires coordinated global action, clear market signals, and robust governance.

A. Economic and Regulatory Mechanisms

Shifting the global energy economy requires policies that reflect the true cost of carbon.

A. Carbon Pricing: Implementing a carbon tax or an Emissions Trading System (ETS) makes emitting $\text{CO}_2$more expensive. This incentivizes companies to invest in low-carbon alternatives and efficiency.

B. Regulatory Standards: Setting strong regulatory standards, such as clean electricity mandates or fuel efficiency standards, drives technological change and ensures market transition regardless of short-term price fluctuations.

C. Incentives and Subsidies: Targeted incentives and subsidies are necessary to accelerate the deployment of nascent, high-potential technologies like $\text{DAC}$ and green hydrogen, helping them reach economic scale.

D. Just Transition: Policies must ensure a just transition, providing financial support, retraining, and community investment for workers and regions currently dependent on the fossil fuel industry.

B. International Cooperation

The carbon crisis is a borderless problem that necessitates unprecedented global coordination.

A. Paris Agreement: The Paris Agreement provides the essential framework, binding nearly all nations to set and meet national climate targets (Nationally Determined Contributions or $\text{NDCs}$).

B. Technology Transfer: Wealthier nations must facilitate the transfer of clean technology and expertise to developing nations, enabling them to leapfrog fossil fuel dependency directly into renewable energy infrastructure.

C. Climate Finance: Significant climate finance must be mobilized from developed to developing countries to fund both mitigation (emissions reduction) and adaptation (coping with inevitable climate impacts).

D. Monitoring and Verification: A robust global system for the monitoring, reporting, and verification ($\text{MRV}$) of $\text{CO}_2$ emissions and carbon removal projects is essential to ensure accountability and track global progress toward net-zero goals.

Conclusion: Securing the Future Balance

The carbon cycle crisis is the most profound challenge facing humanity, driven by the massive and rapid geological perturbation caused by industrialization. Our response must be equally massive and rapid.

The stability of the global climate is fundamentally dependent on the equilibrium of the four main carbon reservoirs: atmosphere, ocean, biosphere, and geosphere.

The crisis stems from the human extraction and burning of vast quantities of geologically sequestered carbon in the form of fossil fuels.

This anthropogenic influx has severely amplified the greenhouse effect, driving global warming and pushing atmospheric $\text{CO}_2$ concentrations to dangerous levels.

The first critical pillar of the solution is rapid emissions reduction, achieved through a massive global transition to wind and solar power, backed by robust energy storage.

The second pillar requires carbon sequestration, using natural methods like reforestation and the adoption of regenerative agriculture to pull $\text{CO}_2$ from the air and store it in soil.

Engineered solutions like Direct Air Capture ($\text{DAC}$) and Carbon Capture and Storage ($\text{CCS}$) are necessary to remove legacy $\text{CO}_2$ at scale and neutralize hard-to-abate industrial emissions.

Effective implementation demands market mechanisms, such as a carbon tax or Emissions Trading System ($\text{ETS}$), to align economic incentives with climate goals.

Global cooperation is vital, requiring rich nations to provide climate finance and facilitate technology transfer to the developing world under the framework of the Paris Agreement.