Introduction: The Dawn of Precision Genetic Engineering

For most of human history, our relationship with our own genetic makeup has been one of passive acceptance, where the complex instructions encoded in our DNA dictated our biological destiny without our direct intervention. Diseases caused by single genetic mutations, such as cystic fibrosis or sickle cell anemia, were tragically inevitable, and the idea of curing them by editing the faulty DNA sequence seemed like pure science fiction. This passive era ended dramatically in the early 2010s with the refinement of CRISPR-Cas9 (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and CRISPR-associated protein 9), a revolutionary gene-editing system adapted from the natural immune defenses of bacteria.

CRISPR-Cas9 provides biologists with an unprecedented level of precision, efficiency, and affordability in manipulating the genetic material of virtually any organism, from microbes to human cells. Suddenly, the capability to make targeted, surgical changes to the fundamental building blocks of life moved from the realm of theoretical possibility to practical reality, offering the tantalizing promise of eradicating genetic disease and dramatically improving crops. However, this immense technological power is a double-edged sword, opening the door to profound ethical, social, and even existential debates.

The ability to edit the human germline—the DNA passed down to future generations—forces society to grapple with moral boundaries surrounding human enhancement and the potential creation of permanent genetic inequality. This technology requires not just scientific rigor but a global consensus on responsible application. This comprehensive guide will dissect the natural history and mechanism of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, explore its life-changing applications in medicine and agriculture, and meticulously examine the complex ethical and societal dilemmas that its power has unleashed upon the world.

Section 1: Decoding the CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism

The CRISPR-Cas9 system is a natural bacterial defense mechanism repurposed by scientists into the most versatile and powerful tool for genetic engineering.

A. The Natural System: Bacterial Immunity

The CRISPR system evolved in bacteria and archaea as an ancient and highly effective immune system against invading viruses (bacteriophages).

A. Capture and Storage: When a virus invades, the bacteria capture small snippets of the viral DNA and integrate them into their own genome at specific locations called CRISPR arrays. These snippets act as a genetic memory.

B. RNA Guide Creation: When the same virus attacks again, the bacteria rapidly transcribe the stored viral DNA into short RNA molecules called guide RNAs (gRNAs).

C. The Cas9 Executioner: The gRNA partners with a powerful molecular enzyme, the Cas9 protein, which acts as a pair of molecular scissors. The gRNA guides Cas9 precisely to the matching viral DNA sequence, where Cas9 cuts the DNA, neutralizing the threat.

B. Repurposing the Tool for Gene Editing

Scientists realized this natural system could be engineered to target and cut any DNA sequence in any organism.

A. The Custom Guide: Researchers design a synthetic single guide RNA (sgRNA) that is complementary to the specific target gene they wish to edit (e.g., a faulty sequence causing disease).

B. The Targeting Mechanism: This sgRNA directs the Cas9 enzyme to the exact desired location in the host cell’s DNA, acting like a molecular GPS.

C. Making the Double-Strand Break: Once targeted, the Cas9 enzyme creates a precise double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA helix at the target site.

D. Cellular Repair: The cell recognizes the break as damage and attempts to repair it using its own repair mechanisms, which scientists exploit to achieve the desired genetic change.

C. Exploiting the Repair Pathways

The final edit—the replacement of the faulty gene—is achieved by manipulating the cell’s natural DNA repair processes.

A. Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): This is the cell’s quick-and-dirty repair mechanism. It often inserts or deletes a few base pairs at the break site, which usually inactivates or “knocks out” the target gene. This is useful for studying gene function or silencing a harmful gene.

B. Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): This is the high-fidelity repair mechanism. Scientists introduce a synthetic DNA template along with the Cas9 complex. If successful, the cell uses this template to precisely fill the gap, effectively replacing the old sequence with the new, desired sequence.

C. Efficiency: The major scientific challenge is that HDR is far less efficient than NHEJ. Improving the efficiency of HDR is critical for achieving precise therapeutic gene corrections.

Section 2: Revolutionary Applications in Medicine

CRISPR holds the potential to transition medicine from treating symptoms to curing the underlying genetic causes of disease, ushering in an era of genetic therapy.

A. Somatic Cell Gene Therapy

This approach involves editing the DNA in the somatic cells (non-reproductive body cells) of a living person. These edits affect only the treated individual and are not passed on to their children.

A. Treating Blood Disorders: CRISPR is showing immense promise in treating blood disorders like Sickle Cell Diseaseand Beta-Thalassemia. Stem cells are removed from the patient, edited ex vivo (outside the body) to correct the faulty gene, and then reinfused into the patient.

B. Fighting Cancer: The technology is used to engineer a patient’s own immune T-cells to be better at recognizing and attacking cancer cells (CAR T-cell therapy), creating a more powerful, targeted immunotherapy.

C. Addressing Viral Diseases: CRISPR is being investigated as a tool to snip the latent DNA of viruses, such as HIV or Herpes simplex virus, out of human cells, offering a potential functional cure.

D. In Vivo Editing: More advanced therapies involve in vivo editing, where the CRISPR components are packaged into delivery vehicles (like viral vectors or lipid nanoparticles) and injected directly into the body to edit cells in organs like the liver or eye.

B. Modeling and Drug Discovery

Beyond direct therapy, CRISPR has become an indispensable tool in laboratory research, accelerating the development of new treatments.

A. Disease Modeling: Scientists use CRISPR to precisely recreate human disease-causing mutations in cell cultures or animal models (like mice) to better understand the progression of the disease and identify biological targets.

B. High-Throughput Screening: The system allows researchers to quickly knock out thousands of different genes in parallel to see which genes are essential for a disease (like cancer) to thrive. This accelerates the identification of new drug targets.

C. Therapeutic Testing: Once a new drug candidate is developed, it can be tested on the CRISPR-edited cells to see if it successfully restores normal function or kills the diseased cells.

Section 3: The Broader Impact in Agriculture and Environment

The speed and precision of CRISPR are transforming fields beyond human medicine, offering powerful solutions to global challenges like food security and climate change.

A. Enhancing Crop Resilience

CRISPR allows for the rapid, precise modification of plants to improve their yield, nutritional value, and ability to withstand environmental stress.

A. Disease Resistance: Scientists can introduce specific edits to make crops (like wheat or rice) immune to devastating blights and viral pathogens, reducing the reliance on chemical pesticides.

B. Climate Adaptation: Genes can be edited to create plants with enhanced drought tolerance or salt resistance, allowing agriculture to continue in increasingly arid or saline environments.

C. Nutritional Improvement: The technology can be used to boost the content of essential vitamins or healthy oils in staple crops, addressing global issues of micronutrient deficiency.

D. Speed of Development: Unlike older methods of genetic modification or traditional breeding, CRISPR allows beneficial traits to be introduced in months, drastically accelerating the time needed to develop new, improved crop varieties.

B. Environmental Applications

The ability to manipulate the genetics of non-human organisms has profound implications for conservation and ecological balance.

A. Controlling Invasive Species: Scientists are developing gene drives—genetic mechanisms that can rapidly spread a specific trait (like sterility) through a target population—to control invasive pests, insects, or rodents in an ecologically targeted way.

B. Disease Vector Control: A major application is editing mosquitoes to prevent them from carrying and transmitting deadly diseases like Malaria or Zika virus, potentially eradicating these diseases in targeted regions.

C. De-extinction (Theoretical): While highly controversial, CRISPR provides the theoretical means to edit the genomes of close living relatives to reintroduce traits of extinct species, such as the Woolly Mammoth, though this raises massive ecological and ethical questions.

Section 4: The Ethical Frontier: Human Germline Editing

The most intense ethical debate surrounding CRISPR centers on its potential application to the human germline—the reproductive cells whose DNA is inherited by all future generations.

A. Defining Germline vs. Somatic Editing

It is critical to distinguish between the ethical scope of the two primary types of human genetic modification.

A. Somatic Editing: Edits made to non-reproductive cells (like blood or liver cells) are non-inheritable. They affect only the patient and carry fewer long-term societal risks.

B. Germline Editing: Edits made to sperm, egg, or early embryos are inheritable. They become a permanent, transmissible part of the human gene pool, affecting all descendants of the individual.

C. The Moral Line: Most international scientific bodies currently endorse somatic cell editing for therapeutic purposes but have called for a moratorium or outright ban on clinical germline editing, citing the irreversible and unpredictable consequences.

B. The Slippery Slope of Enhancement

The transition from editing to cure disease to editing for trait enhancement is the core of the ethical “slippery slope” argument.

A. Therapy vs. Enhancement: Where is the line between fixing a disease (therapy) and improving a normal human trait (enhancement), such as increasing muscle mass, intelligence, or lifespan?

B. Genetic Inequality: Permitting germline enhancement could lead to the creation of a genetic divide, where only the wealthy can afford to give their children superior genetic traits, fundamentally altering the definition of natural human variation.

C. Societal Pressure: Such technology could create immense societal pressure on parents to genetically optimize their children, fostering a new form of discrimination against the unedited.

D. Unforeseen Consequences: Introducing changes into the global gene pool carries the risk of unforeseen genetic and evolutionary consequences that cannot be retracted once they are implemented.

C. The Case of the CRISPR Babies

The ethical debate exploded into reality with the announcement of the world’s first genetically edited babies.

A. Unauthorized Experiment: In 2018, Chinese scientist He Jiankui announced the birth of twin girls whose embryos he had edited using CRISPR to confer resistance to HIV.

B. Global Condemnation: This unauthorized experiment was widely condemned by the global scientific community because it involved germline editing, was non-therapeutic (HIV resistance can be achieved by other means), and breached nearly all existing ethical guidelines.

C. Regulatory Wake-Up: The incident served as a stark warning, accelerating international efforts to establish stricter regulatory frameworks and consensus regarding human gene editing research.

Section 5: Safety Concerns and Technological Refinements

Despite its precision, CRISPR-Cas9 is not perfect, and ongoing research is focused on mitigating the risks associated with the editing process.

A. Off-Target Effects

The main safety concern with CRISPR is the possibility of making unintended cuts in the DNA.

A. Mistargeting: The guide RNA might bind to a sequence that is highly similar, but not identical, to the target site, causing Cas9 to make an unwanted cut somewhere else in the genome. These are called off-target effects.

B. Unwanted Mutations: These unintended cuts can lead to unexpected and potentially harmful mutations in other genes, creating severe health risks for the patient or embryo.

C. Optimization: Researchers continuously work to design more specific guide RNAs and use high-fidelity variants of Cas9 that are less prone to cutting at incorrect sites.

B. The On-Target Risks

Even when the cut is made at the correct site, the cell’s repair mechanism can still lead to undesirable outcomes.

A. Large Deletions: In some cases, the cell’s repair system (NHEJ) can delete very large chunks of DNA near the target site, an error that could disrupt nearby critical genes.

B. Chromosomal Rearrangements: The repair process can sometimes lead to large-scale chromosomal abnormalities or rearrangements, which are known to be carcinogenic.

C. Immunogenicity: In in vivo therapy, the human immune system might recognize the Cas9 protein (which is foreign, coming from bacteria) as an intruder and launch an immune response, neutralizing the therapy or causing severe inflammation.

C. Next-Generation Editing Tools

To overcome the limitations of the traditional Cas9 scissors, scientists have developed smarter, more sophisticated editing tools.

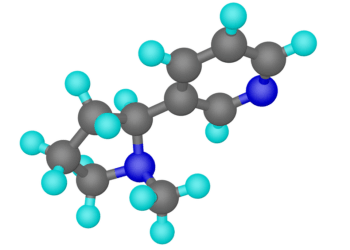

A. Base Editing: This revolutionary technique modifies a single base pair (e.g., changing an A to a G) without creating a double-strand break in the DNA helix. This greatly reduces the risk of off-target effects and large deletions.

B. Prime Editing: Often called the “search-and-replace” tool, Prime Editing uses a modified Cas9 and a complex guide RNA to not only nick the DNA but also directly write in the new sequence, offering unprecedented precision and versatility without reliance on the cell’s unpredictable repair pathways.

C. CRISPR-Free Editing: Newer systems are being developed that move away from the Cas9 protein entirely, using alternatives like CRISPR-associated transposases to insert large genetic sequences with greater safety.

Conclusion: The Ultimate Responsibility

CRISPR-Cas9 is a foundational technology that marks the transition from reading the code of life to actively writing it, presenting humanity with tools of unprecedented biological power. This breakthrough offers a clear path toward eradicating suffering caused by genetic disease.

The mechanism is based on a bacterial immune system, using a guide RNA to precisely direct the Cas9 enzyme to cut a target DNA sequence.

CRISPR has already demonstrated success in somatic cell therapy to treat serious blood disorders and to engineer immune cells for advanced cancer treatment.

In agriculture, the technology is crucial for rapidly creating crops resistant to disease and stress, improving global food security.

The primary ethical red line is human germline editing, as these changes are irreversible and will be passed down to all future generations.

Concerns about off-target effects and the potential for a new era of genetic inequality necessitate strict global oversight and continuous technological refinement.

The development of next-generation tools like Base Editing and Prime Editing promises to deliver the necessary safety and precision for broad clinical deployment.

Ultimately, the future of gene editing is a test of humanity’s wisdom, requiring us to manage this powerful biological tool with humility, prudence, and a commitment to global equity.