Introduction: A New Window on the Universe

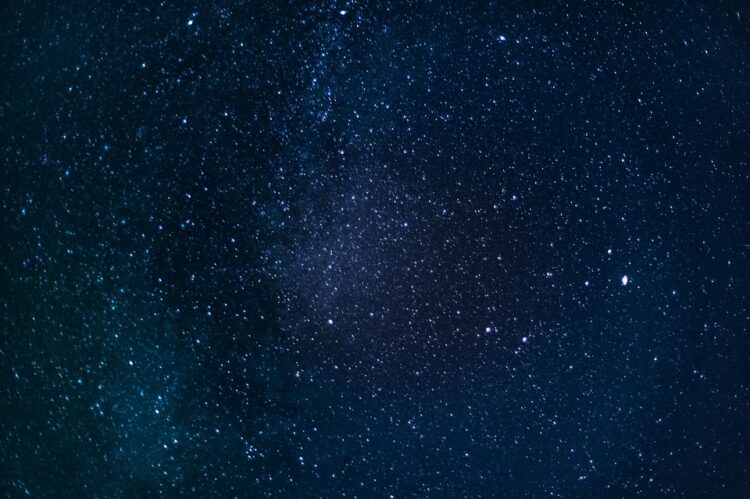

For over three decades, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) provided humanity with breathtaking views of the cosmos, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of galaxies, star formation, and the scale of the universe. However, as revolutionary as Hubble was, its capabilities were inherently limited by its primary focus on visible and ultraviolet light, which often struggled to penetrate the vast clouds of cosmic dust that obscure the most distant and earliest celestial objects. These obscuring dust clouds act as a veil, hiding the critical epoch of the universe—the time when the very first stars and galaxies were born. To truly peer into the universe’s infancy, scientists needed an instrument capable of detecting the faint, stretched-out light from these ancient sources.

This necessity gave rise to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), a massive leap forward in astronomical engineering and capability. JWST is specifically engineered to observe the universe predominantly in the infrared spectrum, the range of light perfectly suited for penetrating dust and capturing the redshifted light from extremely distant objects. As the universe expands, the light emitted by objects billions of light-years away gets stretched, shifting its wavelength from visible light into the longer, infrared range. By operating far from Earth’s heat and orbiting at the Sun-Earth L2 Lagrange Point, JWST remains passively cool, allowing its instruments to detect these incredibly faint thermal signatures without interference.

The successful deployment and commissioning of JWST, launched on Christmas Day 2021, inaugurated a new golden age of astronomical discovery. Its stunning resolution and unprecedented infrared sensitivity immediately began challenging long-held cosmological models, revealing galaxies that were unexpectedly bright, massive, and mature just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. This exploration will delve into the groundbreaking scientific observations made by JWST across four primary domains: the early universe, exoplanet atmospheres, stellar life cycles, and the dynamics of our own solar system.

Section 1: Piercing the Veil of the Early Universe

JWST’s primary mission is to capture light from the first stars and galaxies that formed following the cosmic “Dark Ages,” an epoch previously inaccessible to human observation.

A. The Discovery of Unexpectedly Mature Galaxies

Within months of becoming operational, JWST delivered staggering data that immediately began to challenge established cosmological timelines regarding galaxy formation.

A. Redshift and Age: By measuring the redshift (z) of light, astronomers can accurately determine the age of a galaxy. High redshift values correspond to extreme antiquity.

B. JWST Ultra-Deep Fields: Observations in the ultra-deep fields revealed numerous galaxies with redshifts of $z > 10$, placing their formation mere hundreds of millions of years after the Big Bang.

C. Mass and Brightness Anomaly: These early galaxies were found to be unexpectedly bright, massive, and structurally mature—implying that star formation and mass accumulation proceeded much faster in the early universe than previous models had predicted. This forced cosmologists to reconsider the physical processes governing the universe’s infancy.

B. Understanding Reionization

A critical period in cosmic history, known as the Era of Reionization, saw the universe transition from an opaque, neutral gas state to the transparent, ionized state we observe today.

A. The Cosmic Dark Ages: Before reionization, the universe was filled with neutral hydrogen gas that absorbed visible light, creating a “Dark Age” following the Big Bang’s light (the Cosmic Microwave Background).

B. The Source of Ionization: The energy needed to ionize this vast hydrogen gas must have come from the intense ultraviolet light emitted by the very first stars and galaxies. JWST’s highly sensitive spectroscopy is designed to characterize these first light sources.

C. Mapping the Process: JWST is actively measuring the patches of ionized gas surrounding the earliest galaxies, providing the first direct evidence of how and when the “fog” cleared, allowing light to travel freely across the cosmos.

Section 2: Revolutionizing Exoplanet Science

JWST’s infrared spectrographs possess the sensitivity required to analyze the light passing through the atmospheres of distant exoplanets, opening a new frontier in the search for habitable worlds.

A. Atmospheric Characterization

The telescope uses the transit method combined with spectroscopy to analyze the chemical composition of exoplanet atmospheres.

A. The Transit Method: As an exoplanet passes in front of its host star, some of the star’s light filters through the planet’s atmosphere.

B. Spectroscopic Fingerprints: Different gases in the atmosphere absorb light at specific infrared wavelengths, creating a unique “fingerprint” in the light spectrum. JWST records these minute absorption signatures.

C. Detection of Key Molecules: JWST has already made headline-grabbing detections, including the definitive identification of carbon dioxide ($\text{CO}_2$) and methane ($\text{CH}_4$) in the atmospheres of several gas giants and super-Earths, providing unprecedented detail on their atmospheric structure and chemistry.

B. The Search for Biosignatures

The ultimate goal of exoplanet atmospheric analysis is the detection of biosignatures, chemical compounds that strongly suggest the presence of life.

A. Water Vapor and Oxygen: While water vapor ($\text{H}_2\text{O}$) is common, the presence of substantial free oxygen ($\text{O}_2$) is considered a powerful biosignature, as on Earth, it is constantly replenished by biological processes (photosynthesis).

B. Unexpected Findings: JWST’s high sensitivity has revealed surprising complexity, with some “hot Jupiters” showing unexpected chemical stratification and temperature inversions, forcing scientists to update their models for planetary weather systems.

C. TRAPPIST-1 System: A major focus is the nearby TRAPPIST-1 system, which hosts seven Earth-sized rocky planets. JWST is systematically observing these worlds to determine if any possess stable atmospheres and the necessary chemical conditions to support liquid water.

Section 3: Deep Dive into Stellar Evolution and Birth

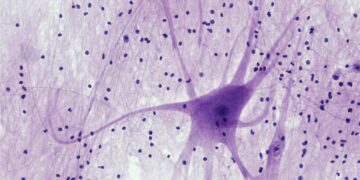

The infrared light sensitivity of JWST allows it to peer directly into the dense, opaque molecular clouds where stars and planetary systems are born, revealing details of the stellar life cycle previously hidden by dust.

A. Imaging Nebulae and Star Formation

Dust is transparent to infrared light, allowing JWST to capture breathtaking, highly detailed images of star-forming regions.

A. The Pillars of Creation: JWST revisited the famous Pillars of Creation nebula. Its infrared image revealed thousands of previously unseen, newly formed stars nestled within the towering columns of gas and dust.

B. Protoplanetary Disks: The telescope can clearly resolve protoplanetary disks—the swirling clouds of gas and dust around young stars where planets are currently forming—providing observational evidence for theories of planet formation.

C. Ejection Jets: Detailed observation of young stars has captured the powerful, supersonic jets of material being violently ejected from the stellar poles during their early, turbulent growth phases, helping to map the forces at play in a star’s birth.

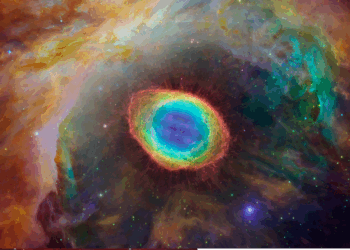

B. Observing the End of Stars

JWST also provides crucial data on the violent and beautiful final stages of a star’s life, including supernova remnants and the creation of heavy elements.

A. Planetary Nebulae: The telescope has captured intricate details of planetary nebulae, the shells of gas ejected by dying, Sun-like stars. Infrared data reveals complex chemical distributions and the structures formed by the interaction of the star’s final winds with the surrounding material.

B. Heavy Element Creation: Supernovae explosions are the primary cosmic factories for creating all elements heavier than iron. JWST’s spectral analysis of these remnants is helping trace the paths of these newly forged elements as they are dispersed back into interstellar space, ready to form the next generation of stars and planets.

C. Dwarf Star Atmospheres: Observations are also focused on the atmospheres of brown dwarfs (failed stars) to understand the transition point between massive gas giants and true stars.

Section 4: Closer Look at Our Solar System

While JWST looks primarily outward, its infrared capabilities also provide unique insights into the cold, distant, and icy bodies within our own solar system.

A. Outer Solar System Bodies

The cold, icy nature of objects in the outer solar system makes them perfectly suited for study by JWST’s infrared instruments.

A. Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs): These small, icy bodies orbiting beyond Neptune hold pristine materials dating back to the formation of the solar system. JWST can analyze their surface composition, searching for the unique infrared signatures of various ices and organic molecules.

B. Comet Composition: JWST’s spectroscopy can analyze the gases sublimating from comets as they near the Sun. This reveals the volatile chemical composition of the comet’s nucleus, providing clues about the chemicals that were delivered to the early Earth.

C. Asteroid Belt: Analysis of asteroids helps characterize the diversity of rock and mineral types in the inner solar system, informing planetary scientists about the chaotic mixing of materials during the solar system’s first few million years.

B. Planetary and Satellite Observations

Even close-up planetary targets benefit from JWST’s unique spectral coverage, revealing atmospheric and surface details previously inaccessible.

A. Mars and the Giant Planets: JWST has captured incredibly detailed thermal maps of Mars, showing temperature variations across its surface and atmosphere. It has also observed the stunning auroras and storm systems on Jupiter and Saturn in unprecedented infrared detail.

B. Icy Moons: A major focus is on the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn, such as Europa and Enceladus, which are thought to harbor vast subsurface oceans. JWST can look for infrared signatures of plumes of water vapor potentially erupting from their icy crusts, directly sampling the ocean contents.

C. Understanding Io: JWST’s infrared imaging is uniquely suited to monitor the intense volcanic activity on Jupiter’s moon Io, tracking the extremely hot spots and the gases emitted by the hundreds of active volcanoes across its surface.

Section 5: The Challenge to Existing Models

The sheer volume and precision of JWST’s data, particularly from the early universe, are compelling scientists to fundamentally rewrite portions of the current cosmological model.

A. Revising Galaxy Formation Theories

The rapid maturity and high mass density observed in early galaxies contradict the previous consensus that large structures should have taken billions of years to coalesce.

A. Accelerated Growth: The findings suggest that the mechanisms for cooling gas, forming stars, and growing supermassive black holes must have been far more efficient in the universe’s first few hundred million years.

B. The Role of Dark Matter: Some theories are now exploring whether the initial distribution of Dark Matter was clumpier than previously assumed, providing larger, more efficient gravitational seeds for early galaxy formation.

C. Seed Black Holes: The early appearance of massive galaxies also implies the rapid formation of Supermassive Black Holes (SMBHs), challenging models of how these central monsters initially formed and grew so quickly.

B. The Interplay with Hubble Data

JWST’s infrared observations do not replace Hubble’s visible light data; rather, they serve as a powerful complement, painting a complete picture of cosmic objects.

A. Combined Imaging: By fusing Hubble’s sharp visible light images (showing hot, established star clusters) with JWST’s penetrating infrared images (revealing the dust-enshrouded birth regions), astronomers gain a panchromaticview of cosmic processes.

B. Age Verification: Hubble identified the locations of many distant galaxies, but JWST’s infrared spectroscopy is required to accurately verify their redshift and age, lending confidence and precision to the most distant measurements.

C. Long-Term Legacy: The combined data sets from both telescopes will serve as the definitive foundation for cosmology and astronomy research for the next generation of scientists.

Conclusion: Redefining Our Cosmic Place

The James Webb Space Telescope represents an unprecedented technological achievement, effectively granting humanity infrared “superpowers” to peer through the cosmic veil of dust and time. Its first years of operation have confirmed its role as a revolutionary instrument, providing data that not only answers old questions but also generates entirely new and profound scientific riddles.

JWST’s extraordinary infrared capabilities allow it to detect the redshifted light from galaxies that formed surprisingly early in the universe.

The unexpected maturity of these ancient galaxies is forcing scientists to accelerate and rewrite existing theoretical models of cosmic structure formation.

In exoplanet science, JWST’s spectroscopic analysis is definitively identifying key atmospheric molecules, including water and carbon dioxide, on distant worlds.

The telescope provides stunning, detailed views into stellar nurseries, capturing the violent processes of star birth and the dispersal of elements from dying stars.

Observations of our solar system are revealing the pristine chemical composition of icy comets and providing high-resolution thermal maps of distant planets and moons.

The data gathered by JWST is fundamentally changing the scale of cosmic history and our understanding of the efficiency of processes in the early universe.

The telescope’s ongoing mission is set to redefine our relationship with the cosmos by detailing the universe’s origin, evolution, and the potential for life elsewhere.